Please click the following hyperlink before reading further; I will not provide any additional information other than that the page serves as a vital context for the discussion that follows: definitely not a lolcat.

Did you click on it? My apologies if you did; rest assured, I linked a lolcat to an UCWbLing blog post for reasons beyond an attempt to elicit spontaneous laughter (or loathing, if you’re a dog person). If you clicked on the link, you likely experienced a moment of uncertainty while the page loaded, unsure whether to expect a lolcat, a hard drive-eating virus, or something else entirely. Chances are you’ve experienced the exact same feeling while conducting online research, surfing the web, or—dare I say it?—illegally downloading music or movies. The uncertainty surrounding hyperlinks is primarily due to the lack of context that surrounds them. Even if the link is given some context as part of a larger work like an article, blog, or podcast, it is often impossible to know the file format or content until it’s too late.

This is precisely the problem that UK publisher and author Mark Boulton discusses in “Sparkicons and the Humble Hyperlink,” a blog entry that expresses dissatisfaction with the limitations of hyperlinks and proposes a few improvements that could potentially change the way we use these important tools as both providers and consumers of online media.

Boulton’s preliminary discussion made me reconsider how vital hyperlinks are to streamlined use of the web. Without hyperlinks, Boulton claims, online media would be significantly more insular:

“…many would say that our ability to link one resource to another via hypertext is what makes the web what it is.”

Without this fundamental tool, not only would it be extremely difficult to directly engage one’s web content with the larger internet community, but from the perspective of the consumer, this lack of interconnection would make it impossible to use the boolean search technology that makes information so readily available at the click of a mouse. Further, the entire web-building and advertising industry would be underdeveloped as hyperlinks lay the groundwork for search optimization and branding efforts. The hyperlink has certainly gained importance and utility with the rise of blogging, podcasting, and social networking, yet virtually no efforts have been made to improve or modify it.

Boulton provides his own examples of poorly contextualized hyperlinks to support his qualms. Chances are, if a user clicks on a link to a ‘video,’ ‘song,’ or ‘image,’ he or she is opening an online can of worms of which the media target is just a small part. Think of all the times you’ve clicked a hyperlink and had to sort through endless ads, banners, memes just to find what you’re looking for. While having a bit of description in the link text certainly helps, it’s usually impossible to determine what is perhaps the most important information about the content: content type, file format, and document size if applicable. The simplest way to solve this problem would be to incorporate all of this “meta data” into the link text as well, but as Boulton notes, such additions are likely to hamper “the ebb and flow of reading long form content.” If my blog post is interrupted by something like this is a hyperlink to a tumblr page covered in large jpeg images that you can scroll past until you find the (6:07) youtube video of Dream Song 14 towards the bottom, you probably won’t read any further.

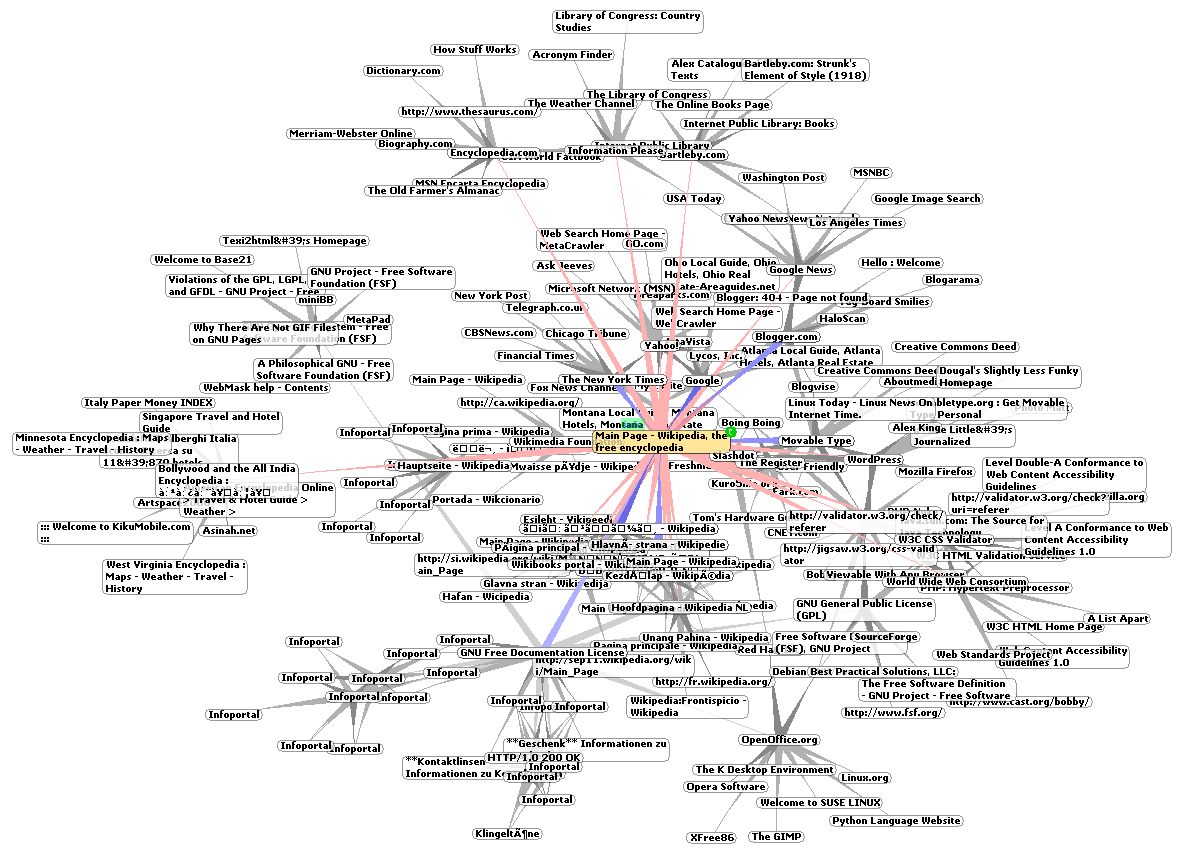

To avoid this issue, Boulton focuses on the potential use of CSS or Javascript icons to provide the meta data the user deserves. He points to Wikipedia and BBC as internet networks that are already using such icons to a degree. Check out the citation links at the end of any Wikipedia article and you’ll notice the nice little icons that make distinctions between website links and file downloads, the file type clearly indicated in the latter case. It’s great to see a bit of progress on the part of these content providers, but Boulton believes they can go further because the icons provide limited meta data and are almost exclusively used for list items when hyperlinks in long form text are just as deserving of their specificity.

Boulton points to Edward Tufte’s discussion of sparklines as a starting point for hyperlink development. A sparkline is a small, complex graphic often imbedded in long form text to provide additional information. According to Tufte, sparklines are not your typical gif or clip art files simply because they are used for more refined purposes:

“Sparklines mean that graphics are no longer cartoonish special occasions with captions and boxes, but rather sparkline graphic can be everywhere a word or number can be: embedded in a sentence, table, headline, map, spreadsheet, graphic.”

Boulton suggests that we improve on the existing technology by combining Tufte’s perspective on sparklines with the BBC and Wikipedia use of in-line icons. While the name suggests (at least to me) a new breed of mechanical opponents for the Autobots to fight in the next Transformers sequel, these hypothetical tools could change the way internet users interact with hyperlinks. Boulton defines the sparkicon as “a small, inline icon with additional link meta data to describe either the content and/or the behaviour when the user clicks the link.” These indicators would function similarly to what we already see on Wikipedia and BBC pages, but would be more conducive to placement within visual or text-based content.

He provides a few examples of what sparkicons might look like and what they could communicate. For visual content hyperlinks, a simple ‘full-screen’ or ‘external site’ sparkicon provides important information about how the user will experience the media. Specific to video links, Boulton provides examples of sparkicons that indicate the video length and the number of views, meta data a user rarely has access to before the point of no return. Other potential sparkicons could indicate aspect ratio and resolution for video content.

While my lack of technical expertise made me a feel a bit intimidated when I first started reading Boulton’s article, I was soon put at ease with his conversational tone and jargon-free vocabulary. The argument made me think about how far online media has come, but also how much more progress can be made. I can imagine how instrumental the sparkicon would be in reducing online research time, allowing the user to quickly skip past all the junk boolean search terms can find, increasing the efficiency and accessibility of the entire process. We can only hope for the day when web surfers will no longer suffer from hyperlink post-click anxiety, uncertain whether they’re about to stumble upon the perfect article or come face to face with yet another lolcat.

One reply on “What Have I Clicked On? : The Uncertainty of the Hyperlink, the Ambition of the ‘Sparkicon’”

Interesting article Richie, it’s nice to see that the wild frontier of the internet is starting to come into focus. Maybe now my mom will venture past the AOL front page.