Screenplays are tricky. Not only are they expected to evoke strong emotion and entertainment in a reader, but they require a multitude of specific formatting conventions. Because of this, it can be easy to feel intimidated by a screenplay at first glace.

As strange as a screenplay appears, it is simplistically complex and beautiful in its own right.

Navigating the interaction between tutor and screenwriter can be difficult, especially since screenplays rarely make an appearance within the walls of the Writing Center. In the following post, I hope to clear up some of the ambiguity surrounding this written form of storytelling!

format

A single page of a screenplay can hold various foreign elements for the peer-writing tutor: strange indentations, character descriptions, capitalization of names, dialogue, etc. While analyzing the basics of screenwriting format, it is important to note that “white space” within the document is normal and, in fact, encouraged.

Due to the nature of screenplays in a fast-paced entertainment industry, writers will often make their screenplays light and easy to read in its initial draft. That way, the editor or publisher can quickly scan their work, assess its potential, and decide to produce.

For the tutor, they are presented with a much less arduous financial task: reacting and revising. To help with major formatting revisions, here is a bullet point list of several screenwriting conventions:

- Scenic descriptions will typically begin with either “INT.” or “EXT.”, breaking down the interior and exterior of the shot.

- Location names are capitalized within the screenplay to emphasize the change of location when it occurs.

- Character names are ALWAYS capitalized in order to help the actor find their line in the cold read. Yes, they are even capitalized in the action lines and scenic descriptions.

- In dialogue, character names are centered and capitalized, with their actual text indented closer to the left side of the page.

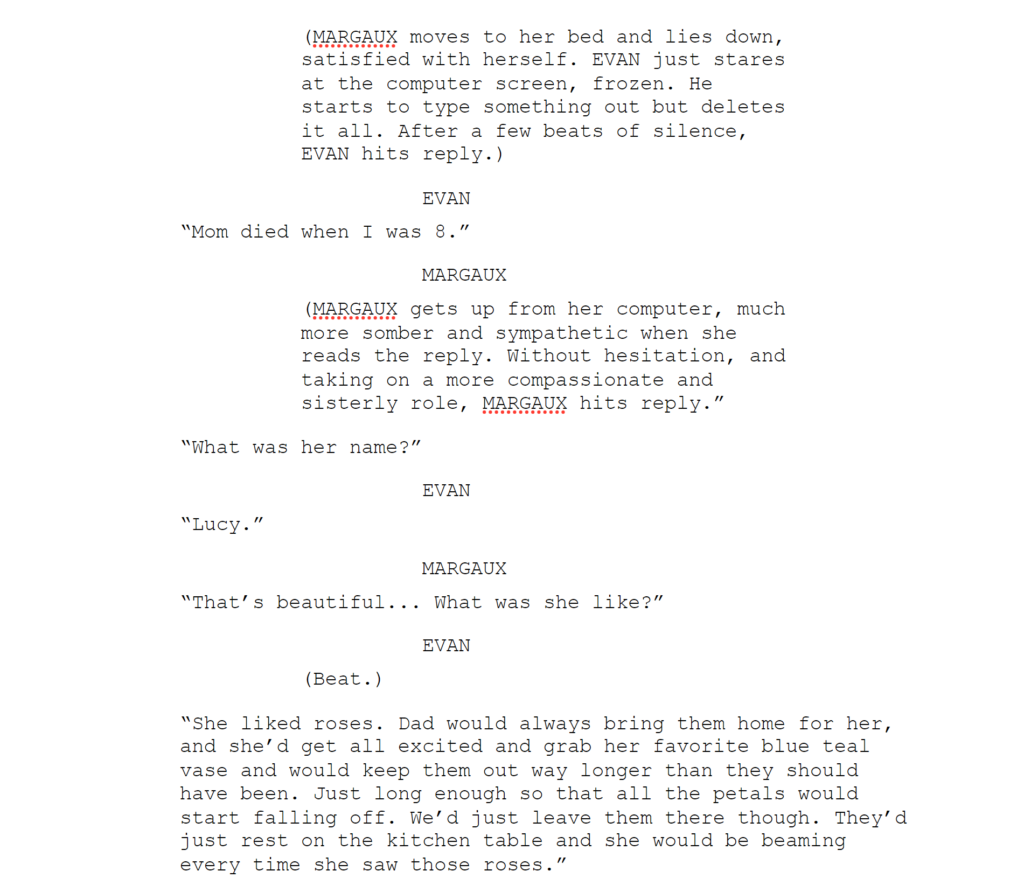

While this may sound tricky, there are plenty of model screenplays on google to reference in times of doubt! In addition, here is a picture of a screenplay that I wrote in high school which can be used as an additional reference:

While I am confident in my formatting here, I can’t say the same for the plot…

story

In terms of providing feedback on a screenplay, this is perhaps the most important agenda item a peer-writing tutor could address with a writer. The story forms the framework upon which everything else in the narrative can be built. Therefore, it can be likened to a “global concern” in Writing Center terms.

Sabrina Michaels, a TTS students pursuing her minor in screenwriting, says this when asked about the most important aspects of screenwriting: “You are basically playing a balancing act between writing the story you want to see and not writing as a director.”

To help with this specific agenda point, Michael Ferris brings up an iconic phrase in his article for the Writer’s Digest: “SIMPLIFY YOUR STORY, COMPLICATE EVERYTHING ELSE.”

An elaborate story line will lead the reader away from the clarity, depth, and arch they need in order to immerse themselves into the world of the screenplay.

dialogue

Dialogue in a screenplay ideally walks the line between clever and witty interplay, marinated in substantially powerful monologues. Navigating this section of a screenplay can be especially difficult since the writer intends to parallel their dialogue to the reality of the world they are crafting.

Because of this, responding naturally to the draft is very insightful for the writer. With that in mind, sharing a screenplay and receiving feedback on the “readability” and “reality” of the writing can be an incredibly vulnerable experience for the writer.

Therefore, treating the appointment with empathy and hospitality creates the ideal atmosphere of respect and professionalism to work in.

Some factors to consider while looking at the writer’s dialogue include:

- Subtext – what are the characters saying versus meaning?

- Differentiating Characters – are there specific ticks/impulses that make a character unique?

- Establishing Emotional Stakes – why does a certain cinematic moment hold weight at this point in the script?

audience

At the end of the day, providing feedback on a writer’s screenplays allows the tutor to play the virtual role of the “audience”. Therefore, this disproves the notion that a screenplay is an individual process. Rather, it is built upon multiple stages of drafting, revising, and incorporating feedback.

To aid the writer in this process, it may be helpful to either work with the same tutor on a weekly/monthly basis or, contrastingly, work with a different tutor every time they receive feedback. That way, the writer is reaching a diverse audience at each stage of their drafting process.

Screenwriting involves a full-blown writing process and more. Students brainstorm research, write character biographies, visually construct scenes, critique the writing of peers, and must be able to effectively write dialogue as well as description.

Lawrence Baines & Micah Dial in “Scripting Screenplays: An Idea for Integrating Writing, Reading, Thinking, and Media Literacy“, published in The English Journal in 1995.

reaction

The screenwriter, like any writer, wants a second set of eyes. They want to model the reaction that their writing will receive through the lens of a peer-writing tutor. While this may induce pressure to have the “right” reaction, I hope this blog post reminds you that there is no such thing.

Art seeks to create a reaction and to provoke something in the viewer, no matter what that “something” is. As hard as the writer may try to influence this process, the viewer or audience member will think what they think, believe what they believe, and trust what they trust.

As a peer-writing tutor, what a joy it is to be one of these audience members!

Richard Brody, in his article “Screenwriting Isn’t Writing” for the New Yorker, mentions American screenwriter Wells Root as he worked with Howard Hawke, director of “Tiger Shark”:

“We usually met each day after breakfast, down on the beach. We would sit on the beach, in the sun, and talk over the story, and break now and then to take a swim…. He would never sit down with a paper and pencil. It was all talk, and then I would go and write it.”

In writing center terms, this kind of feedback session parallels that of a Face-to-Face appointment – without the swimming, of course. Screenwriters deeply benefit from this style of feedback since using conversation as a means for communicating honest and helpful feedback heightens and clarifies future drafts.

where to go from here

While providing feedback on screenplays may seem daunting, I hope this blog post is helpful in dispelling your concerns about this illustrious and ambiguous art form.

I will leave you with a quote from Stephen King because that, truly, is the best way to end a blog post such as this.

“Timid writers like passive verbs for the same reason that timid lovers like passive partners. The passive voice is safe. The timid fellow writes “The meeting will be held at seven o’clock” because that somehow says to him, ‘Put it this way and people will believe you really know. ‘Purge this quisling thought! Don’t be a muggle! Throw back your shoulders, stick out your chin, and put that meeting in charge! Write ‘The meeting’s at seven.’ There, by God! Don’t you feel better?”