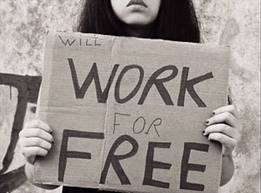

Unfairness, thy name is unpaid internship. During one conversation appointment this week, I fell into something of a difficulty: having to explain why I had done so many unpaid internships. My conversation partner, a finance graduate student, had already had a paid internship with an ample (if not exactly generous) stipend, and thought it was strange when I said I’d never had a paid internship. In the past four years, I’ve worked for several companies in several roles, but always unpaid and always with a paying retail or office job on the side so I wouldn’t run my bank account into the ground. I’ve spoken with other students in humanities or writing programs over the past few years and many of them reported similar experiences (with the exception of those who only did unpaid internships and let the budgetary chips fall where they may). I’m willing to bet that most of our readers in LA&S can relate, and most science or business students are thinking I’m crazy for accepting unpaid work. For me, the question becomes: why does the unpaid internship seem to be only the plague of humanities or writing-based fields? Does it actually do anything, other than drain our bank accounts? And what can we do to change it?

There are a couple of good reasons why the unpaid internship is not a constant across every academic or career field. The first difference between a finance or accounting internship and, say, working for a newspaper, is the tenor and expectation of the internship. The internships I have worked have been explicitly not a career stepping stone at the same company, so it made sense to work at them for a few weeks and then take my newfound experience elsewhere. For other internships, it seems to be a sort of proto- or lower-paying entry position that then leads to being hired at the same company. Some internships treat their interns like employees from the start, but rarely have I seen this with writing-based internships. Instead, the gift of your tenure is the experience, and maybe the option of calling the employer for a reference later on.

Companies that offer writing-intensive internships are also, by and large, not wealthy. An investment firm might be able to take on a new employee as an intern; a small publisher barely has enough to pay its full-time editors, much less a trainee. Moreover, these are creatives that we’re talking about, so a less settled or irregular, less formula-based hiring approach is par for the course. On some level, I understand why writing-based internships are less reliable as potential career stepping stones and less likely to pay – the fields they purport to introduce an intern to are also less stable and often pay less. We are supposed to work to satisfy a creative urge or to do what’s in our hearts, not to make money.

Is this how it has to be, though? Writing and English and journalism and history students want to get paid for their knowledge, like everyone else. Even entry-level writing jobs in these fields often require at least two years of experience in this type of publishing or that type of technical writing, and they often pay very little. A contract-writing company was found this past week to be offering prospective employees fractions of cents per word, a base demand of 40,000 words per week, and at the same time demanded a comprehensive application with multiple pitches and samples. Why is the writing and publishing industry not more nurturing of the newbies? The best way to ensure thoughtful and creative writing is to provide a network or support system for your writers, but in this case, finance and accounting jobs far outstrip creative or humanities fields. Writing is too often seen as both incredibly easy (anyone can write, and we will pay them the bare minimum to do it) and as an arcane, difficult science (one that requires years of experience and knowledge of every computer program on the market, and then there’s SEO…) – and unpaid internships are the result. Aspiring writers must know everything but expect no pay past the boss ‘putting in a good word’ for the amount of training they put in.

On some level, it makes sense. The career fields that most attract humanities students or writers are also often based around relationship-building, and so a good relationship with an established professional in the industry can be the best takeaway for an unpaid intern. However, if we don’t start valuing the work that writers do and finding a way to reward their struggles, the cycle will simply continue and desperate writers will continue to accept the only experience they can get – unpaid internships. I’ll cop to not knowing how to fix this struggle – how about you, UCWbLers?