Although it is arguably the most important stage of the writing process, revision is often misunderstood or avoided altogether. Revision means thinking critically about the choices we’ve made as writers, how those choices will affect our audiences, and determining whether that satisfies our purpose for writing. In my experience as a student and tutor, revision is often reduced to proofreading for errors or simply “cleaning up” the first draft. As we close off this academic year, let’s not let unexplained quotes or run-on sentences hold us back in our final papers!

Writing center scholarship suggests that when we take revision into our own hands—and when we receive feedback from others—it’s best to follow a hierarchy of concerns when it comes to which weaknesses of the draft are addressed first. In the checklist included below (adapted from Bean’s Engaging Ideas), the elements of a strong piece of writing are listed from highest priority consideration to lowest. While grammar and style are important for establishing clarity and credibility with your reader, you wouldn’t want to spend time rewriting sentences in a paragraph that gets cut in the final draft.

Revision as a Collaborative Process

Collaboration with peers and advisors during the revision process can be highly valuable. Because you want to think critically about how your writing will affect your audiences, having a different set of eyes offer outside, nonevaluative feedback can inform much stronger changes to the final draft.

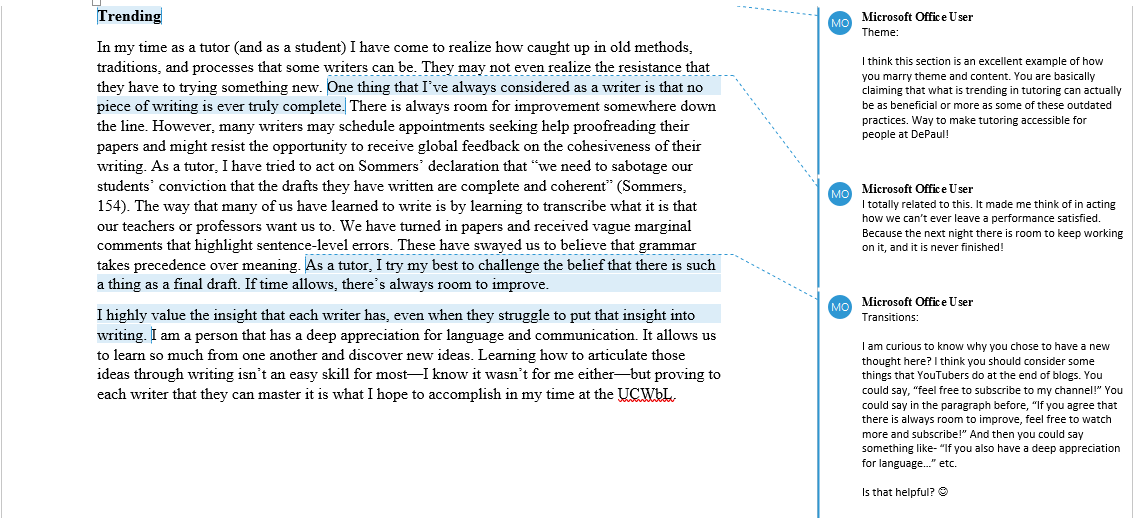

As Writing Center tutors, we offer specific yet transferable reader-based feedback, especially in written feedback appointments. While I’m shy about sharing my work, I have found these comments immensely helpful. This example is from a written feedback on my tutoring philosophy for my UCWbL ePortfolio. While this first draft is not very good, my tutor highlighted the strengths of my writing and the choices that she found effective. For example, rather than use evaluative language like, “I really like this!” she writes, “I think this section is an excellent example of how you marry theme and content.” I was able to use these strengths to inform my corrections of weaknesses that she constructively identified. In addition to asking meaningful questions for me to consider in my next draft, she also makes multiple suggestions for revision.

As Writing Center tutors, we offer specific yet transferable reader-based feedback, especially in written feedback appointments. While I’m shy about sharing my work, I have found these comments immensely helpful. This example is from a written feedback on my tutoring philosophy for my UCWbL ePortfolio. While this first draft is not very good, my tutor highlighted the strengths of my writing and the choices that she found effective. For example, rather than use evaluative language like, “I really like this!” she writes, “I think this section is an excellent example of how you marry theme and content.” I was able to use these strengths to inform my corrections of weaknesses that she constructively identified. In addition to asking meaningful questions for me to consider in my next draft, she also makes multiple suggestions for revision.

Independent Revisions

While collaboration is useful for gaining audience insight, it is also important that we take ownership of our own work, too. Identifying and working on any weaknesses or errors you find before sharing your draft with someone allows them to maximize their feedback on issues in the draft that you didn’t catch yourself.

Things to Consider

- Organization: The order in which our claims, ideas, or themes appear can really impact how well your audience understands or engages with your purpose for writing. Taking the “building block” approach to writing that I mention in my drafting post can lead to a disjointed body of text. If you’re unsure whether your current organization is the most effective, try printing out your draft and cutting it up so each body paragraph is separate. You can slide these pieces around and read them out loud to determine which order sounds the most organic.

- Style: Writing style is a bit of a broad term that asks you to consider the deliberate writing choices that are informed by both your individual voice as a writer and the broader context in which you’re writing. When revising for style, you might want to think about the conventions of the genre and your purpose for writing. Are you writing to persuade, inform, tell a story, or something else? How might your language use and word choice affect your purpose?

Additionally, when revising for style, you might want to consider conciseness. A common habit that I’ve recognized, especially in my own writing, is taking on flowery language for academic writing. While the language might sound nice, being repetitive or overly descriptive in a way that does not contribute to the overall argument can become distracting or confusing to your reader. To improve this in my own writing, I’ve used the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s handout on Revising for Conciseness. This resource offers tips on identifying ineffective wordiness and making your sentences more succinct. - Proofreading: As you move toward your final revisions, proofreading is an important step in assuring your clarity and credibility with your audience. Although many word processors have built-in grammar checks, they don’t often catch every error. Being deliberate and conscious of spelling, grammar, and punctuation when we write can make us better writers. Personally, I love using the Purdue OWL’s resource on Proofreading for Errors. This handout identifies some of the most common sentence-level errors with explanations of the grammar rules and examples for revision.

Revision is critical for fulfilling our writing purpose prior to its publication. When we submit our work or share it with broader audiences, we want to ensure that it is the strongest representation of our thoughts, expressions, ideas, and ourselves. Taking the time to be deliberate in our writing will pay off, and we ultimately become better, stronger, and happier writers!