There has been a great evolution in my mind concerning the concept of graffiti. When young, I associated it with a disrespectful ugliness that surfaced on trips to see my grandma on the south side of Chicago or my aunt in Logan Square. Overpasses and freight trains were covered with bold, clashing primary colors in a distended script that conjured hood rats and foggy alleys in my mind.

As I grew older though (despite Daley’s Graffiti Blasters), I began to consider it an art form and a kind of social protest against Lockean edicts of private property. This actually became a frequent argument with a friend of mine. Tagging was neither cool nor art. It was impudent and a burden. The City of Chicago’s official website corroborates this thought reminding its citizens that “[g]raffiti is vandalism, it scars the community, hurts property values and diminishes our quality of life.” I could say that the use of comma splices might also hurt our community, and a little copy editing might help your argument, but I won’t. Instead, I will simply ask: is this entirely true?

The urges to tag, I think, are all twisted and coiled up with the urges to write. We write for a few reasons. The most obvious reason is that our teachers tell us to. There is an authoritarian demand from the academy for students to write. Yes, this is different from the demands a gang will have on its members to mark their haunts on the streets, but all I am noting is that the ideas of demand and obligation run along the same trajectory in a gang as in the academy. And what is the academy really other than a bunch of scholarly toughs inducted into basement offices in a uniform of elbow pads and leather mules, given grades and red pens as their tools of enforcement?

The other motivations to write are what I’m more interested in here though. We write to comment on what we see. We write to put our ideas out into the public realm and see how others respond. We write to make a mark. Thus, are tagging and conventional writing really so different?

This brings me to the real subject of this post, which is to share with you a bit of vandalism I saw on the Blue Line this week. No, it was not your typical run of the mill gang marking; nor was it some disparaging drawing near a female model’s mouth. Rather it was a critical comment that 1) forced the viewer to reevaluate the function of writing on public spaces and 2) reminded of the way people sell and think in our society.

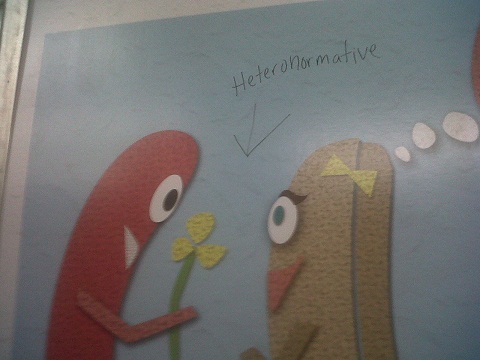

Some of you may have seen the sexually suggestive ads that GrubHub puts around the city: a man and a woman in bed seeking “Something Spicy!” and more recently, a hot dog (must I even note that this image is phallic?) and a bun. The hot dog presents a flower to the bun just as she thinks, “I hope he brought condiments, too.” Har-dee-har-har. They’re talking about sex! Hot dog sex! Too clever GrubHub, too clever. If I weren’t a vegetarian, I would never eat hot dogs the same way again.

Well, one CTA rider did not think this image clever at all. S/he was so disappointed that s/he dug into hir purse/pocket, grabbed a pen, and decided to “scar the community” and “diminish our quality of life” by writing the following:

What do you make of this written commentary dear reader? Certainly, the graffiti is an adequate appraisal of the ad. The comedy of the ad relies on a heteronormative perspective, and the tagger urges us to note the hegemony of this perspective. Are the gender biases that s/he points out a problem? Did s/he diminish our quality of life, or is GrubHub diminishing ours? Further, is it art? One thing I can say for sure is that this vandal wrote. S/he put her ideas out into the public realm, and this reader commented. What do you think?

3 replies on “To Tag, or Not to Tag”

I must respectfully challenge a few of your points here. First, on the nature of graffiti. As a former graphic designer and art director, I have no doubt that much of the graffiti I see is typography of the highest order. I am often astounded by the strength and confidence of line and the beauty of the concept. However, that gives no one the right to “mark” someone else’s property without their permission. If you want to tag someone’s garage door, ask them, pay them,set up a contract with them. In lieu of that, you are a criminal, regardless of your writer’s motivation. When I was in art school, we had to buy blank canvases and sketch books!

Regarding the Grub Hub ads, I see them, and I think I understand the motivations of their creative team. They are trying very hard to appeal to an under-30 demographic that is fully committed to technology and has no problem with the cost of ordering takeout food on a more-than-occasional basis. They try also to be provocative, within the regulations of transit advertising. Whether or not the old “hot dog in the bun” analogy is problematic is a personal decision (by the way, the bun is a symbolic as the hot dog!) it is certainly heteronormative. But that’s not against the law, and I suspect only the most militant gay rights activist would find it offensive or inappropriately intrusive into our collective public life. Personally, after taking DePaul’s Intercultural Communications class, I think it’s kind of funny!

If we were serving on a jury, we would probably consider the severity of the crime. Should writing “heteronormative” on a poster on the CTA be punished at the same level as an 8-foot spray painted tag on the side of someone’s house? I would guess we would say no. But we would probably be in agreement that in our society, you don’t have the right to mark something that does not belong to you. What do you think?

Do I dare challenge our conception of “property”? Why yes, I certainly do. Part of what I find so interesting about graffiti is how public it is. It’s present. It’s in your face! Doesn’t matter if it’s in a stall, on the train, or smeared across the side of the building: graffiti ends up being for both the tagger and the viewers. Consequentially, it reminds us that whatever’s viewable to the rest of the world is not “private” and untouchable. Graffiti laughs, “Property? Ha! What a ridiculous scale,” and defaces the very idea that the image of a wall, or an ad, can be “owned.” We can talk back and add to the discussion with the public! In many ways, ads, which thrive on viewers, belong to the public at least as much as agent. In this case, the tagger is reminding us that the interaction with the ad doesn’t need to be one way conversation. Besides, who can’t appreciate the succinct textual analysis this tagger provided us with?

Like any other art, I think there are “higher” and “lower” orders of graffiti. Artists like Banksy not only create beautiful images but engage in a form of political activism. When I was living in New Orleans, I was blown away by some of the stencil graffiti he did there. In one piece, two National Guard soldiers can be seen hoisting a television out of a window; in another, Abraham Lincoln is seen as a homeless man, pushing a cart full of belongings. Especially in the context of post-Katrina New Orleans, these images challenge dominant ideologies by juxtaposition, irony, and humour. Bravo!

Of course, not all graffiti does these things. A lot of it seems to say nothing more than “I was here.” I remember going to work in New Orleans one day and seeing three or four city blocks tagged in a really obnoxious way. It was frustrating to see how hard businesses and individuals were working to recover from the storm, only to have their hard work screwed with by what were probably a bunch of bored teenagers with nothing much to say.

So for me the distinction between “high” and “low” graffiti lies within the context of the tag, the skill of the artist, and the potential for activism.