Code-switching is a hot topic on university campuses these days. Not only are educators and writing tutors talking about it, but people are also examining how they code-switch in their everyday lives. But there’s a new hot topic in town, code-meshing, and it’s here to replace code-switching for good.

In his influential book on the subject, Other People’s English, Vershawn Ashanti Young describes code-switching as a strategy “where students are instructed to switch from one code or dialect to another… according to setting and audience” (1-2). So a student who speaks African American Vernacular English (AAVE) at home and Standard American English (SAE) at school is code-switching every time they walk through the classroom door.

But this strategy has increasingly come under criticism. Scholars like Neisha-Anne S. Green have documented the mental and emotional toll that code-switching can take on people who speak marginalized dialects like AAVE (10). Is there an alternative to this prescriptive, assimilationist approach?

Recently, scholars have championed an alternative known as code-meshing, in which students are encouraged to blend their dialects, instead of separating them based on societal expectations. Young explains,

“Code meshing what we all do whenever we communicate—writin, speakin, whateva. Code meshing blend dialects, international languages, local idioms, chat-room lingo, and the rhetorical styles of various ethnic and cultural groups in both formal and informal speech acts.”

(“Should Writers” 114)

Notice what he did there?

Switching or Meshing?

So, code-switching and code-meshing are two strategies that multilingual writers can use to choose between different dialects or codes. They might not seem all that different from a bird’s-eye view, but the difference lies in the motivation behind that choice.

In Other People’s English, linguist Rusty Barret describes the linguistic origin of the term code-switching. Researchers made a distinction, he explains, between situational code-switching, in which a switch is made based on environment or context, and metaphorical code-switching, described as, “using two languages in the same context to exploit the context-meaning associated with each language” (29). In other words, switching back and forth between codes within the same sentence, based on whatever is most effective in saying what you’re trying to say.

In recent years, code-switching has come into the vernacular as the situational variety. As a result, Young proposed the term code-meshing to describe, from an educational perspective, the rhetorical choice to blend dialects within the same work.

But why is code-meshing so preferable in the classroom, or in the tutoring center? Shouldn’t we be encouraging writers to speak and write the way their bosses and professors expect them to, and leave their native dialect in the home?

It’s important to recognize the inherent “separate but equal” assumptions underlying this line of thinking (Green 21). By telling writers that they can speak their native dialect at home but only SAE at school or work, we are still endorsing the idea that one dialect is better than another, if in a more subtle way.

Furthermore, rules about which dialect should be used in a given context may actually hinder a writer’s ability. Young writes, “Teachin speakin and writin prescriptively… force people into patterns of language that aint natural or easy to understand” (“Should Writers” 112). When not peering through the patronizing lens of assimilation, prescriptivists might find that speakers of marginalized dialects and natural code-meshers are perfectly capable of expressing themselves— but in their own vernacular.

Examples of Code-Meshing

Unencumbered by a lot of the high-minded assumptions about “proper speech,” pop culture is one high-profile medium that has always embraced multilingualism and code-meshing. Indie pop band Kero Kero Bonito frequently employs melodic English choruses interspersed by Japanese rap verses:

Jamila Lyiscott delivers a code-meshed presentation in verse in her Ted Talk about the importance of code-meshing, showcasing the clever rhetorical devices that are available to a speaker jumping between three dialects:

Young’s article “Should Writers Use They Own English?” is an example of code-meshing, blending AAVE, SAE, and technical language regarding linguistics and education. It offers a tantalizing glimpse into the growing field of code-meshed academic writing: https://ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1095&context=ijcs.

And this blog curated by the University of Rochester’s Writing, Speaking, and Argument Program offers an extensive list of academic works that employ code-meshing: http://swang.digitalscholar.rochester.edu/code-meshing/category/in-academia/.

Centering Code-Meshing in the Tutoring Process

Here at the University Center for Writing-based Learning, we care a lot about using our position as tutors and educators to advance an agenda of equity and justice. As we have seen, language can be an effective tool of oppression, and as an institution devoted to fostering and developing language skills, it is our responsibility to counteract this oppression in every way we can.

In my years as a tutor, the UCWbL has done a great job of teaching the principles of code-meshing and accommodationist tutoring strategies. One prominent recommendation for educating people about code-meshing, the discourse community map, is an exercise we have done many times at the UCWbL (Green 23).

But personally, I don’t feel I’ve done a particularly good job of putting the principle of code-meshing into practice in my tutoring. From sentence structure to word choice to quote integration, so much of my go-to advice in appointments would be more accurately classified as encouraging code-switching than code-meshing.

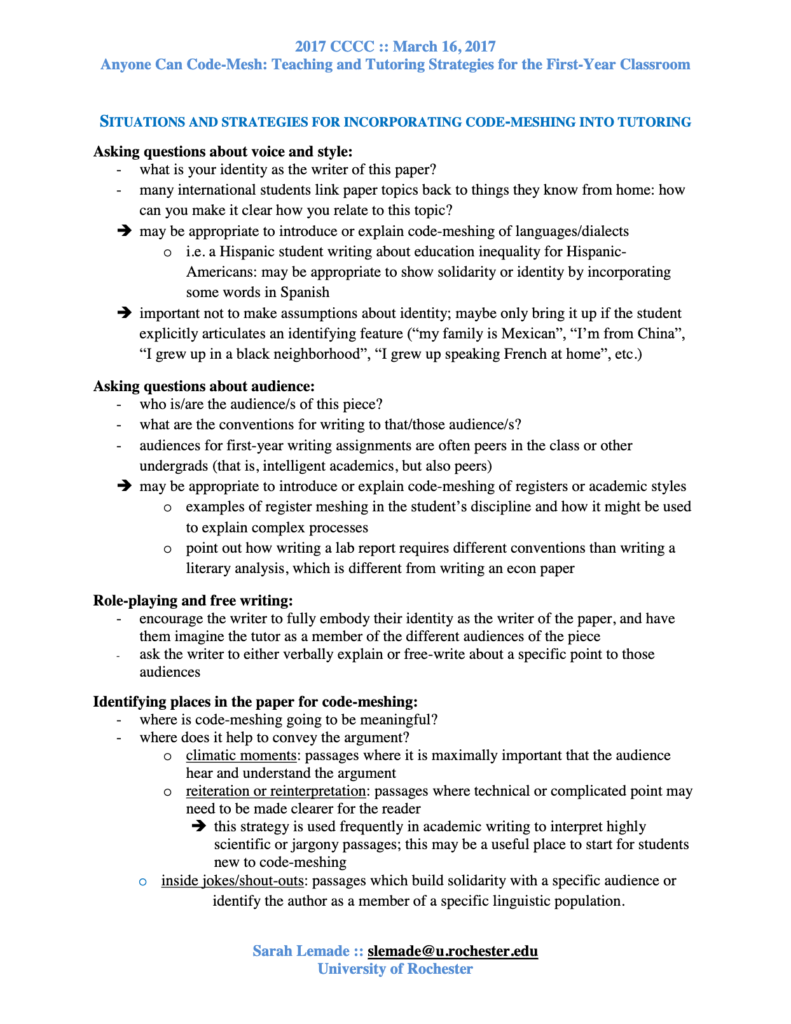

So, I wanted to lay out some concrete plans for how to encourage writers to code-mesh. Below is a handout from Sarah Lamade, a former writing tutor at the University of Rochester, with questions to ask a writer and strategies to suggest during a tutoring appointment.

Lamade encourages tutors to spell out the theory behind code-meshing for a writer, and articulate some of the areas where code-meshing might improve their writing — she identifies climactic moments, reinterpretation, and inside jokes as three prominent ones.

Similarly, Green leads by example by laying out the rhetorical options for the writer, and then letting them make decisions about which code to employ:

I talk to the student about audience and how some people might view their writing and misjudge their capabilities and label them as dumb or having a “cognitive deficit.” I use the language “as a reader this is what I see” “some readers may interpret this as . . .” “you as the author have choices.” Then and only then—after I’ve informed the student—do I say “well what do you want to do?”

(Green 17)

Significantly, this approach may sometimes entail encouraging the writer to say or write things that may be “grammatically incorrect,” or inadvisable by traditional Strunk & White standards. This may be an adjustment for some tutors, and can certainly be an adjustment for me.

Finally, I would encourage tutors to consider Young’s imperative that we help people approach writing from a descriptive perspective: “Instead of prescribing how folks should write or speak, I say we teach language descriptively. This mean we should, for instance, teach how language functions within and from various cultural perspectives” (Young 112).

Works Cited

Green, Neisha-Anne. S. “The Re-Education of Neisha-Anne S. Green: A Close Look at the Damaging Effects of ‘A Standard Approach,’ the Benefits of Code-Meshing, and the Role Allies Play in this Work.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 14, no. 1, 2016, np.

Lamade, Sarah. “Incorporating Code-Meshing into Tutoring.” Code-Meshing Pedagogy. University of Rochester, 27 Feb. 2018. http://swang.digitalscholar.rochester.edu/code-meshing/suny-cow/suny-2016/incorporating-code-meshing-into-tutoring/

Young, Vershawn Ashanti, et al. Other People’s English: Code-Meshing, Code-Switching, and African American Literacy. Teachers College Press, 2014.

Young, Vershawn Ashanti. “Should Writers Use They Own English?” Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 12, no. 1, 2010, pp. 110-118.

Discover more from UCWbLing

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.