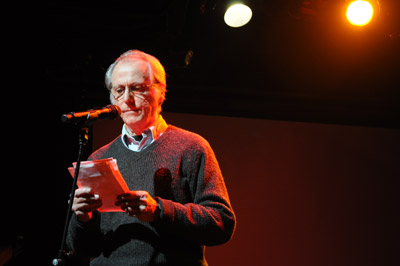

This week, the Chicago Public Library Foundation awarded novelist Don DeLillo the Carl Sandburg Literary Award, and to mark the occasion, DeLillo appeared at the downtown Harold Washington Library last night to read and discuss his latest work, The Angel Esmeralda, a collection of short stories. It was an illuminating discussion. Donna Seaman, the moderator, asked DeLillo about his influences and themes, but there were also many insights into DeLillo’s process as a writer.

This week, the Chicago Public Library Foundation awarded novelist Don DeLillo the Carl Sandburg Literary Award, and to mark the occasion, DeLillo appeared at the downtown Harold Washington Library last night to read and discuss his latest work, The Angel Esmeralda, a collection of short stories. It was an illuminating discussion. Donna Seaman, the moderator, asked DeLillo about his influences and themes, but there were also many insights into DeLillo’s process as a writer.

You hear the adage all the time in creative writing guidebooks: write about what you know. Yet the appeal of DeLillo’s fiction is the opportunity to join in experiences that one could hardly imagine. His casts of characters include 9/11 survivors, Lee Harvey Oswald, astronauts, child prodigies, and rock musicians–so what do you mean “write what you know?” On this point DeLillo struck a middle ground, explaining that lived experience “flows more easily” into the fiction writer’s craft, and perhaps inspires fiction more readily than contrivances. So, writers: don’t settle for writing only what you know, but use your own experiences as the imaginative basis for questions that could very well lead you anywhere.

Readers of DeLillo will know that there is a lot of looking that goes on in his fiction. His characters gaze at paintings, watch experimental films, marvel at statuettes that fit snugly in the palm of one’s hand.

Likewise, Seaman asked DeLillo about his relationship with art and the role art plays in his work. He said in fact his own relationship with art began rather artlessly. As adolescents he and his friends were always lurking around their neighborhood movie theaters, but then when he grew up a little more, DeLillo saw his first European film, and was mesmerized. Filmmakers like Truffaut and Godard showed him that film could do what novels do—that modern art in general could do what any novel could.

These influences, he said, “seeped into” the kind of language he would use as a writer. While other writers, and good ones too, were crafting an “essay-like fiction,” DeLillo had a conscious desire to “write in three dimensions,” as he put it, taking an intensely visual approach to crafting scenes. He knows he has succeeded when he can identify what he calls a “metaphysical connection” between the vision of the scene and the language used, as though he were restoring the direct relationship between signifier and signified. He revealed that to this day he uses a manual typewriter when he composes. The process works, he said, because as the words appear “I read them, consider their meaning, look at them,” treating words and letters as though they were visual art, and just as one learns a new script in another language , he is seeing the words and their parts for the first time.

That, he said, is his relationship with art. “There’s not much I can say,” DeLillo concluded, “except it does affect me.”

Seaman then asked about the kinds of conversations DeLillo’s characters have, and about his style of writing dialogue more generally. He explained that in novels like The Names and Cosmopolis he had aimed deliberately for stylized and mythic-sounding interactions, either because the setting inspired it (as with The Names) or the thematic matter called for it (as with Cosmopolis). In other cases he aims for utmost realism, and is often surprised at how slang can seem so expressionistic in print when it we hardly marvel at its quality when we hear it.

What future remains for language, dialogue, and the novel generally? DeLillo repeated his famous assessment that novelists have ceded their ground to radicalism and even terrorism. “Terrorists have now taken over the territory that used to belong to novelists,” he said, and the need has never been more urgent for fiction that can once again voice social critique and mobilize peaceful popular protest. But where does fiction now stand in US and global culture? And what impact is technology leaving on the novel’s form? These are very difficult questions, DeLillo said. The novel, he is certain, will remain one of “the most challenging and most rewarding” forms of expression we have, but he wonders how technology will change what writers write—“Does poetry need paper?” Who will be left to read it? Will writing fiction develop into a closed-circuit practice, something somebody may do for herself or a few close friends? With the omniscience and omnipresence of the internet helping the fiction writer along, what new kinds of fiction will we see? “I wish,” DeLillo said, “I believed it would be terrifically interesting, but I don’t know.”

Discover more from UCWbLing

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.