You think you have it bad? I certainly thought so. Like many writers, I have a love-hate relationship with our trade. My composing process is riddled with false starts and fitful bursts with long breaks in between, what T.S. Eliot called “a hundred visions and revisions.” Other writers make it seem so effortless, and I spent plenty of time feeling bad for myself. But now I’m cured.

You think you have it bad? I certainly thought so. Like many writers, I have a love-hate relationship with our trade. My composing process is riddled with false starts and fitful bursts with long breaks in between, what T.S. Eliot called “a hundred visions and revisions.” Other writers make it seem so effortless, and I spent plenty of time feeling bad for myself. But now I’m cured.

I recently picked up The Swerve, Stephen Greenblatt’s Pulitzer- and National Book Award-winning foray into book culture of the middle ages and the early European Renaissance. Thomas Cahill in How the Irish Saved Civilization famously showed how Europe’s monasteries preserved the Greek and Latin classics to be unearthed in the early modern period. But what strikes me about Greeblatt’s account of medieval times is just how miserable it was to be literate.

That’s because most monasteries were hardly the quiet, contemplative outposts of erudition and learning that we might imagine them to be. They were definitely quiet, that’s for sure, and isolated too. But they were places of intense control, and the monks themselves were constantly subjected to intense surveillance.

The fundamentals of a syllable, the verbs and nouns shall be written for him and if he does not want to, he shall be compelled to read. (Rule of St. Pachomius 139)

“Compelled to read?” we book-lovers ask. “Why would anybody need to be forced to read?” Well, as Greenblatt shows us, because this was no mere pastime. The Rule of St. Pachomius continues:

Above all, one or two seniors must surely be deputed to make the rounds of the monastery while the brothers are reading. Their duty is to see that no brother is so apathetic as to waste time or engage in idle talk to the neglect of his reading, and so not only harm himself but also distract others.

This apathy, religious authorities believed, was a disease, the “noonday demon” (incidentally, my noonday demon is the first of several daily caffeine crashes). The surest way of keeping the demon at bay was the unrestrained use of force.

If such a monk is found–God forbid–he should be reproved a first and a second time. If he does not amend, he must be subjected to the punishment of the rule so that the other monks may have fear.

As Greenblatt explains, “The symptoms of psychic pain would be driven out by physical pain,” which could even include prolonged beatings.

So let’s be real. All of us writers, whether in college or thereafter, will despair of writing at some point. Perhaps we can’t help it. But let’s offer up some gratitude to our monastic antecedents for all the ordeals they underwent for being literate. After all, they did suffer so that we would have it easier. Here’s why.

As Greenblatt explains, the monks’ rigid, prayerful reading habits meant that the monasteries must have books in large supply”

Reading was not optional or desirable or recommended; in a community that took its obligations with deadly seriousness, reading was obligatory. And reading required books.

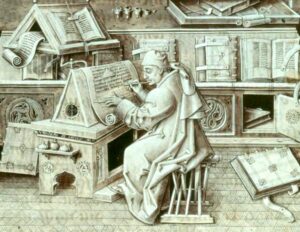

Hence, the monasteries were not only repositories of literacy, but of writing as well. Most had a single chamber, the scriptorium, dedicated solely for the activities of the scribes, who with tireless and painstaking effort copied tens of thousands of texts, many from antiquity, preserving them for later generations. But as with reading, writing was enforced with the same strict measures.

Scribes were at the mercy of the monastery’s librarian. The librarian would confer favor upon lucky monks or wrath upon the wayward, giving well-honed pens and rulers to the fortunate and punishing the error-prone with low-quality parchment. These miserable monks would often vent their frustration in the margins of whatever they were copying:

“…Thin ink, bad parchment, difficult text…”

“…Thank God, it will soon be dark…”

“…For Christ’s sake, give me a drink…”

Now don’t get me wrong: it may very well be possible your teacher assigned that 25-page annotated bibliography just to spite you. But at least they can’t force you to use a piece of parchment that’s too hairy to write on. That’s what I call progress.

Discover more from UCWbLing

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.