Most—if not all—of us tutors are used to rhetorical analyses: looking not so much at what an author is saying, but rather how they say it. However, what we’re less used to is applying this same practice to the spaces around us.

Performing a rhetorical analysis on a space can be particularly illuminating of the ecologies we find ourselves in. It can show us the assumptions and ideologies which underlie the foundations we walk on. Moreover, understanding the spaces around us allows us to figure out how to utilize and/or transform the space into a place that serves our purposes.

In the case of the Writing Center, understanding the space of our office can foster an understanding of what it means to write, tutor, and revise. In this blog post, I offer a rhetorical analysis of the UCWbL’s Lincoln Park office space in order to better understand the ideologies which ground our behaviors as tutors.

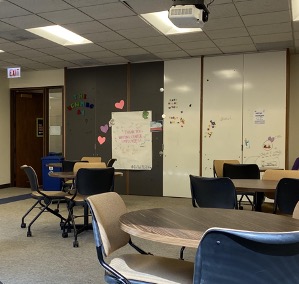

So, let’s explore, the main room.

Here, we can see the material surroundings which guide our work. We have round tables with two to three chairs apiece, whiteboard walls with magnets, and artwork hung about.

The small circular tables with two to three chairs apiece imply that revision is a small-group activity. Circles, with their lack of edges, bring people together. Yet the table’s small capacity size and the few seats they have exclude people by marking boundaries as to who is allowed to be involved.

This spatial arrangement marks the work that is done there—revision—as a collaboration, but denotes borders to the collaboration process.

Imagine instead the main room was organized as a conference room.

More people would be involved, and perhaps the input of a varied audience could produce stronger overall revisions, but the efficiency of the tutoring process would be diminished.

Moreover, the intimacy of working closely on a paper would be decreased, overshadowed instead by the amount and stratification of the tutors present. Therefore, the rhetorical analysis of the UCWbL’s space illuminates that exclusion is used insofar as it provides space for collaboration.

If this seems tricky, as in “how in the world does exclusion help collaboration,” that is okay. We must think more closely about who is involved in the tutoring process and who is left out.

Importantly, the exclusion is not of a particular group of people.

We see in the UCWbL core beliefs that everyone is a writer, and therefore everyone within DePaul can submit to the Writing Center. Where the exclusion comes into play is in the tutoring session itself. By marking the boundaries of who is involved in the tutoring process (the writer and the tutor) with the circle tables, we see that revision and collaboration take on a more intimate setting of closely working with a paper.

Going back to the main room, the whiteboards, markers, and magnets show that the UCWbL is an interactive space. We work in a place where we imbue the very walls with meaning.

This not only fosters collaboration by providing the tools for us to work together, but also shows that tutoring is an active process for us to be engaged in. We must think then about who is engaged in the interaction of the space. Much of what appears on the walls—such as notes to other tutors, drawings, and essay outlines—is originated by tutors, but not writers. This material practice can be rhetorically reproduced in our tutoring practices. We can use the example of our walls to examine how to be better tutors.

When I am tutoring, I find it easy to be the one metaphorically writing on the walls. I take control of the marker and magnets and occasionally see the writer’s paper as an object for me to write up. While this directive approach has its purpose, it is not fitting in every situation.

I have found much more fruitful tutoring sessions when I make the interaction a two-way street. Taking a step back and letting the writer mark up the walls—their paper—puts the writer in the driver’s seat. Thus, we learn that our job as tutors can become not to mark up writers’ papers, but rather to guide them through how to do it themselves.

Ultimately, through this rhetorical analysis of the spatial and material arrangement in the LPC office space, we can attest that the UCWbL is a collaborative and interactive space. The circle tables and their few seats teach us that revision at the UCWbL is marked by exclusion—but an exclusion with the purpose of improving the quality of feedback. And, the whiteboard walls teach us not only how we’ve imbued values and beliefs, but how to better our tutoring practices.

This ideology of collaboration and interaction is manifest in our material surroundings and guides our work as tutors. To illuminate what guides you in other areas of your professional and personal life, I encourage you to continue performing rhetorical analyses of the spaces around you.

What messages do your surroundings bear? How do they speak to you when you don’t even realize you’re listening?

Discover more from UCWbLing

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One reply on “How Space Talks”

I love the concept of taking a step back and letting the writer right on the walls. I think that provides a lot of creativity for the writer as well as experience.