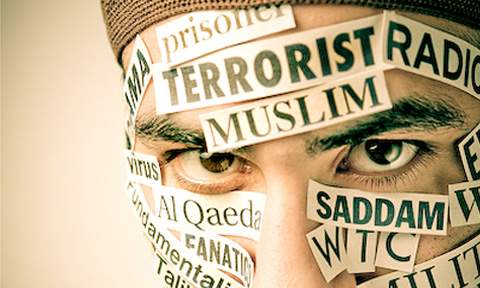

When I go running on Belmont Avenue, I feel like I belong. Skateboarding with my flat mates off Wilson, it’s casual. My presence is primarily ignored, sometimes enjoyed, and occasionally screamed at – markers of a city kid. And although I’d like to believe some suave aspect of my personality determines this, the reality is that others perceive me as default – inoffensive – because I’m a white male. I was reminded of that reality this week at Conversation & Culture when an ELA student from a Middle-Eastern country relayed his friend’s (also of Middle-Eastern origin and appearance) frustrations: he felt as if everywhere he walked in Chicago, some people looked at him as if at any moment he might rip open his shirt to reveal a river of bombs. He doesn’t feel default; he feels helpless as he tries to embrace a country and culture that looks at him with unease.

We arrived at this topic after beginning with some chat about the new Great Gatsby movie. One student pointed out that stories about affluent people often portray them as happy, and she used the words “too happy.” The standard literary response came up: Gatsby illustrates the hollowness that comes with searching for meaning in materialism. What spawned from this though was a less routine topic, more relevant to the lives of many ELA students: representation in the media.

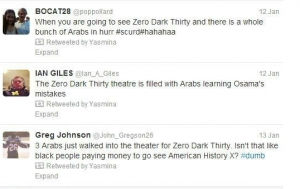

Many months ago, my relative – who shall remain nameless – had just watched Zero Dark Thirty, a film about the capturing of Osama bin Laden. After listening to his testimony on the film’s seriousness, I said I had little interest in watching, as it was likely jingoistic propganda, blinded by unwarranted American patriotism to the individuality of Middle-Easterners. He was immediately defensive and said, “That’s not fair. It does not shy away from criticizing the American government.” While that may be true, it doesn’t negate the stereotyped representation of Middle-Eastern people and Muslims (which often and incorrectly functions as a euphemism for Middle-Eastern) as angry, democracy hating, terrorists. It definitely does not negate the stream of tweets that came out around the movie’s debut

The last one even managed to diversify its racism.

Not every American feels this way. Unfortunately this personal perspective does not translate to many films, TV shows, or commercials depicting dynamic, non-stereotype characters of Middle-Eastern dissent. The same may be said of the representation of all people of color, of women, of LGBTQ peoples, generally all those who are not heterosexual, cisgendered, able-bodied, white males. The faces of our brothers and sisters from Saudi Arabia, Iran, Afghanistan, Kurdistan, and many other countries implicitly define the word terrorist for many Americans. Our media propagates this false understanding and we perpetuate it every day, if not in the form of explicit racism, than certainly in silence. That’s self-maintained ignorance that fails to acknowledge the individuality of several students at Conversation & Culture, and millions of other people. That man I mentioned earlier loves Chicago, and Chicago can love him if it so chooses. If we may lower ourselves to playground logic for a moment: don’t be a meanie, everybody just wants to be friends.

Discover more from UCWbLing

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.