There’s nothing more frustrating than not being able to articulate a simple point – in any language. I struggle enough trying to formulate coherent sentences in French, my second language; the other day I said that “it cried” instead of “it rained” (classic rookie mistake).

Yet the constant shift between my second language and my native language has birthed a surprising new challenge: the inability to remember specific words and phrases in English! My mother refers to this dilemma as “an issue with word retrieval,” attributing it to her age. Even though she exaggerates (she is, as Beyoncé would belt, “flawless”), I can’t use that as an excuse. At 20, I should have reached the peak of my mental fitness, but I’m lagging along. Maybe it’s all the chocolate croissants I’ve devoured – their name does have a quite literal connotation in English: “pain au chocolat.”

It’s as if I’m in language limbo: vestiges of English and French swirl around in my mind, waiting to be delivered to the sentence, their promise land. I pray for them, but some of them are irretrievable, while others fling sporadically from my mouth like sinners thrown into the second circle.

This happens in the most embarrassing of times, like during an interview for an internship. In describing my background in mentoring, I couldn’t recall that thing that a peace project was supposed to do. If I had thought of the word “promote” or “educate” in English, I could have easily translated it and made a somewhat sophisticated comment. Yet all I could say was “peace? peace for the world” in French, which was nothing more than a reiteration of the interviewee’s question of “why did you do this peace project?”

Yes, the recipient often understands the gist of the phrase, but there’s something about not communicating the whole meaning, in its entirety, that makes the speaker feel shortchanged or underrepresented.

With a second language, people learn to expect to lose a shred of meaning in translation. The most aggravating case, however, is when conversing with a fellow English speaker and not having anything productive to say, proving yourself to be an unfun, stammering idiot.

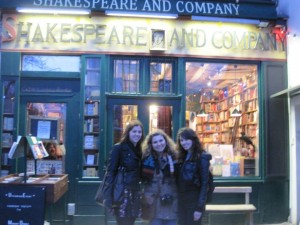

Recently, fellow UCWbLer Micki Burton came to Paris, so she, Elizabeth Gaughan and I convened for a mini UCWbL reunion. Amidst all our experiences evading aggressive bracelet venders and the like, we were still able to hold some meaningful conversation (inspired in part by our rendez-vous at Shakespeare and Co.)

While the sustained periods of English speaking provided much joy and laughter, it also served as testament to how my speaking abilities have plummeted. Well, maybe I was never very articulate, but other words besides, “I know, right?” and “that’s ratchet” used to come to mind. Why are these the words that stick? It’s possible that pop culture has carved out a niche in my brain where 2Pac lyrics and “How I Met Your Mother” references cozy up to one another and thrive. But has this excavated all room for normal conversation?

Last week, my dynamic between French and English was put to the test at the Conversation Club. It had streamlined its structure a bit: we operated on ten-minute intervals, switching the language with each gentle reminder from the coordinator. Because there was an influx of French students this time around, the coordinator wanted to ensure we were speaking English. It worked out well that I brought Micki along, hoping we could speak English for the majority of the time.

This should have been a walk in the park for the English tutor (we are known for our infamous CMWR Walk and Talks, namely to parks and public spaces). Thanks to my experience at the UCWbL, I’m familiar with all the major tools to promote language acquisition, including how to address issues with word retrieval: use synonyms, provide a description, or develop an example. Much like revision, though, this applies much more smoothly to others than to oneself; I may or may not have used a tutoring shift to justify my own chronic procrastination (and I’m not the only one.)

With this hypocrisy in mind, I entered a gauntlet of my worst linguistic fears. The result surprised me: when the “French speaking” period ended, instead of just floundering in English, I would use French words sporadically to fill the gaps. Astounded as I was, French became my lifeline. Usually, I feel guilty when having to supplement my French with the occasional English word; the inverse, however, bolstered my self-esteem and made me feel like a “vrai connaisseur des langues.”

In the succeeding week, I attempted to use my dual knowledge to my advantage. Because a certain mastery of French is the ultimate goal here, my reliance on it must, at the very least, signal that I’m making some progress here.

I know this can be dangerous. Reliance on another language can lead to a piece-meal comprehension of not only one, but two modes of communication. Especially in a monolingual workplace, the option to revert to another language may not exist.

I consider myself lucky to be studying in such a bilingual environment. Word-swapping may serve as a quick-fix until the problem subsides. In the meantime, I’ll have to start practicing what I preach: use synonyms, examples, etc. In retrospect, maybe my host family appreciated the poetic connotations of “it cried,” especially in light of how I felt while saying it.

Discover more from UCWbLing

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.