If you have any friends who are creative writers or have ever been in a creative writing class, chances are you’ve been asked to critique or comment on someone else’s creative writing. It can be a challenging experience. How do you respond to (perhaps critique) a writer’s story without offending them? Where do you even begin, and what do you comment on? Tutors who work with creative writing pieces face these same challenges, so whether you’re a creative writer yourself or someone who reads other people’s creative writing and gives feedback (tutor or not), this post is for you.

When working with stories—creative fiction, fan fiction, or otherwise—it’s a little hard, I’ve noticed, to offer constructive feedback; many readers are often under the impression that their personal opinion can easily offend the writer if, say, they didn’t understand something in the writer’s work, or interpreted the writer’s idea as something completely different from the author’s intended purpose. And the reader worries about telling the writer these kinds of impressions and risking hurting their feelings.

While it is good to be sensitive when responding to a writer (whether they’re writing fiction or nonfiction), fiction pieces require just as much intensive feedback as any other piece of academic writing, with rules that are essential to each piece—no matter the context of the story. For the reviewer, the most important element to giving feedback is: dramatize your experience as honestly as possible. Your opinion, even if it’s on a smaller part of their work, can make a huge impact to the piece as a whole.

There are five general, but important, areas to remember when offering feedback on creative writing: character, plot, setting, conflict, and resolution. Among these 5 areas are also a few subcategories that apply to the writing style specifically; language, structure, and voice.

So, let’s break it down on what things to look for when responding to creative writing.

CHARACTER

The players of the story—the major, or minor, stars. These little guys help further the story along, either in a positive or negative way. Here are some tips to remember when critiquing characters:

- Every major character must want, or desire, something—whether immediate or some deeper desire; this is usually to make them more 3-dimensional. They don’t necessarily have to get what they want, but there should be some indication, or strive, towards it.

- Every major character must change/develop, or have the opportunity to change, in some way. If Johnny was confronted with the option to save a dog or let it get run over, which option would he choose? And how does either option affect his character as a whole?

- Every character, whether major or minor, must be an active participant in the story somehow. If a character is named but doesn’t have any purpose to the, plot then it’s safe to assume they can be trashed or re-purposed.

PLOT

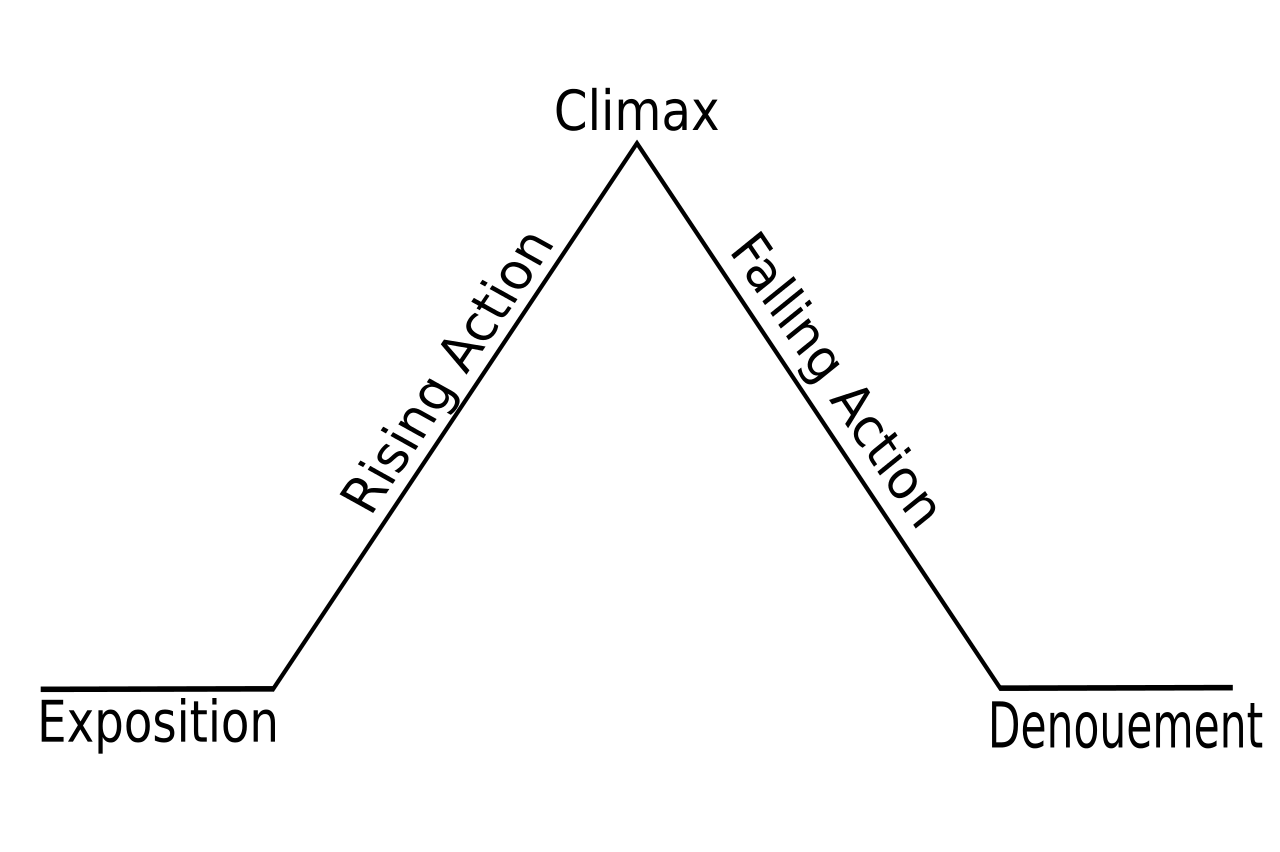

The purpose of the story, why it’s being told, is very crucial to identify ahead of time. This should be the epic journey (or epic, at least, to the reader maybe) that the character(s) embark on. In each plot-line, it should include rising action, which is referred to as conflict and resolution.

Conflict

- Is there a clear “argument”, or problem, that occurs in the story? Is it man vs. man? Man vs. nature? Man vs. society? Man vs. self? How believable does the conflict feel? Does it work well?

- If working with a shorter piece, like a chapter of a story, ask the writer to tell you a little bit about the plot as a whole. From there, you can most likely assess how the chapter fits in with the rest of the story.

- How does the build up of the conflict feel? Does each event or scene in the piece play an important contribution to the climax? Where is the climax?

Resolution

This is one of the harder points of the plot to achieve, considering it’s difficult to pinpoint when the events that follow the climax are too much or too little. There’s almost no happy medium, but a resolution should do exactly as its namesake implies—it should resolve the conflict of the piece, and any other areas, that might need addressing. Are all of the loose ends tied? Were you left with any major confusion about the plot, disregarding personal interpretations of themes & meaning?

SETTING

Where the story takes place is just as crucial as you would expect, and there are typically two elements to setting: physical location and location in time. These can usually be determined by asking two questions: what’s the main location (either city, nation, or planet) and the time period that the story takes place?

Setting, itself, isn’t too common to critique, but in order to be effective, it should make sense in terms of the language and character. If a story is written in the 19th Century, what would be appropriate for that character to say? To dress? To feel about certain issues?

After all of these 5 elements are accounted for in your feedback, that’s when you can start looking for other things, like the writing itself!

I mentioned before that there are three other areas that apply mainly to the writer’s style as a whole: voice, language and structure. Honestly, this is the fun part (in my opinion) where you can make some suggestions and interpretations you got from the text. Voice and language are basically one and the same and refer to the writer’s style itself. What lines stick out to you that seem like they’re unique to the writer? Pointing these out can help the writer strengthen and further develop their writing style as a whole.

Structure refers to the arrangement of both events in the story and the way the story itself is written. Let’s say a character mentions a memory; would this work better or more effectively as a flashback? Should the scenes in the story be moved around? Should the story be told out of order? All of these are concerns of structure.

Reading and reviewing a writer’s work of creative fiction really is no different from responding to a normal academic paper—it’s only a slight twist! As long as you remember that your opinion does matter to the writer and that it’s okay to make suggestions to the writer based on your interpretations of their work, you’ll be fine. After all, it’s up to them what changes they decide to make based on your feedback. All you have to do is offer your honest opinions as a reader, and you’ve done your part!

Discover more from UCWbLing

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.