Last week, I talked about the writing process from a very broad perspective: prewriting, drafting, and revising. With a holistic view of the steps that go into developing a strong piece of writing, and with final papers looming on the horizon, I think it could be useful now to look at one stage at a time, starting from the very beginning.

Prewriting can determine the strength of any project, from an APA research paper to a 4-line poem. The more time that we spend preparing ourselves for what we want to write and how we want to write it, the greater the impact we can make on our readers. While we may realize its importance, prewriting is still the most daunting and commonly avoided stage of the writing process for many of us. But it really doesn’t have to be! Identifying strategies that fit our needs as thinkers, learners, and writers will ultimately help us produce stronger, more authentic work.

We all practice a variety of prewriting strategies whether we realize it or not. This can look like a standard outline or mind map—which I discuss more later—but it can also be reviewing notes, discussing, writing a list of questions, or sitting quietly, just thinking about the project. These are great strategies to get your mental gears turning, but often they aren’t treated as “valid” prewriting practices. When we acknowledge the validity of any strategy that generates more ideas or adds depth, shape, and credibility to our writing, we take ownership of our process and build a stronger foundation for our drafts.

Not all of these strategies involve writing itself, but I find it very helpful to do some writing—even if what you write doesn’t immediately make sense. Writing allows us to at least attempt to articulate and visualize our ideas outside of our heads, which can make the development of an argument—or identifying our purpose for writing—much easier. But what do you write?

Let’s say that all you know about this project is the overarching topic: whales. You might start by talking to a friend about what you might write, like the anatomy of whales, different species of whales, and their historical usage. Where do you go from there? As a tutor and a writer, there are three “traditional” approaches that are among the most effective methods for extrapolating on our initial concepts: researching, mind mapping, and outlining. Sure, we’ve all probably seen these before (and maybe were forced to use them against our will), but hopefully you will be convinced to give them another chance before you write your next draft.

Researching

Many of us may not begin researching until after we’ve decided our argument, but conducting a broad search can help us refine our ideas and provide stronger evidence to support them. We might be guilty of cherry-picking sources because our research wasn’t based on the discourses that currently exist. Researching across different fields, historical periods, and genres can help you develop a better sense of what has been said and how you might synthesize it in your own words. A better-informed discussion can lead to a much stronger paper.

Google Scholar and the DePaul Library Research Guides are my go-tos for conducting preliminary searches. On Google Scholar, I take advantage of the “cited by” and “related articles” links under each result. These can be useful for learning how one author’s work is being engaged with by others and how you might contribute to their discussion. The DePaul Research Guides, meanwhile, make it easy to narrow your search to one field or to experiment with the many different lenses to see your topic through. If you need help with library research, you can also consult a reference librarian for expert research advice.

Mind-Mapping

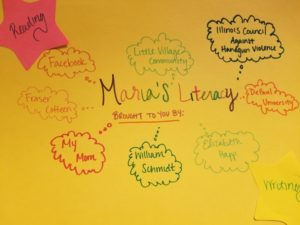

You might be familiar with mind-mapping as a brainstorming strategy from middle and high school, writing one topic in the center of a page and drawing “branches” of related subjects. I had never found making mind-maps, or word webs, particularly informative, and their spatial limitations often left me feeling disorganized and overwhelmed. Ideally, mind-maps can help you visualize the connections between your central argument and the claims, reasoning, and evidence that will be used to support it. I didn’t realize that I wasn’t taking full advantage of this strategy until I was required to construct one for a class using the website MindMeister. This innovative site allows you to keep your idea maps organized, color-coded, and as extensive as you want them to be; they can also be collaborative. For a great example of a collaborative map, check out the one my group made on Pan!c at the Disco’s “Girls/Girls/Boys.” This prewriting strategy is great for identifying overlapping or recurring themes and ideas without the stress of organizing the writing just yet.

You might be familiar with mind-mapping as a brainstorming strategy from middle and high school, writing one topic in the center of a page and drawing “branches” of related subjects. I had never found making mind-maps, or word webs, particularly informative, and their spatial limitations often left me feeling disorganized and overwhelmed. Ideally, mind-maps can help you visualize the connections between your central argument and the claims, reasoning, and evidence that will be used to support it. I didn’t realize that I wasn’t taking full advantage of this strategy until I was required to construct one for a class using the website MindMeister. This innovative site allows you to keep your idea maps organized, color-coded, and as extensive as you want them to be; they can also be collaborative. For a great example of a collaborative map, check out the one my group made on Pan!c at the Disco’s “Girls/Girls/Boys.” This prewriting strategy is great for identifying overlapping or recurring themes and ideas without the stress of organizing the writing just yet.

Outlining

Outlining is my personal favorite prewriting strategy, but it is also one that I find many writers hesitate to try. Outlines are a way to formally organize the ideas brainstormed by the other prewriting methods. While there is no rule for how extensive or detailed your outline should be, I find that taking the extra step to include pieces of evidence makes the drafting process much quicker and easier. As a tutor, one of my favorite practices is helping writers organize their ideas into outlines during the appointment. In a panic about taking the next steps in the writing process, writers will describe to me what they think their central argument might be, and as they talk I transcribe those ideas into an informal outline. This strategy allows writers to avoid the stress of finding the “right words” and simply get their ideas out onto the page.

I’ve found that many of us don’t know how far along we’ve come in our prewriting process until something gets written down. Finding a method that allows you to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the information you’ve gathered on the topic—be it claims, reasons, evidence, context, etc.—can provide more structure when drafting and, hopefully, help you write a much stronger draft. So, rather than staring at a blank screen as you come to write those final papers, give one or more of these strategies a try. Happy Writing! (:

Discover more from UCWbLing

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.