What a writer wants is, I would assume, akin to what Christina Aguilara posits in what a girl wants: fulfillment or whatever. The education research done by Laurel Raymond and Zarah Quinn about writing center tutoring sessions brings up good questions about how we as tutors know if we are fulfilling writers. It touches on factors of importance, but the jury is still out on whether or not it made us happy, or set us free, though it did lead to introspection.

Raymond and Quinn’s study set out to understand and define their role as a writing center for those who seek out their services by answering four questions that look at common concerns of the writer and how effective tutors are at answering them.

The writers of the study focus on these questions in particular for their study: What writing concerns do writers bring to tutoring sessions, what writing concerns do tutors address? How do common writer concerns and common tutor concerns differ in distribution? When writers ask for help with a writing concern, to what extent does the tutor address this concern in the tutorial? That is, how often is the writer’s specific concern fulfilled? Partially fulfilled? Not fulfilled?

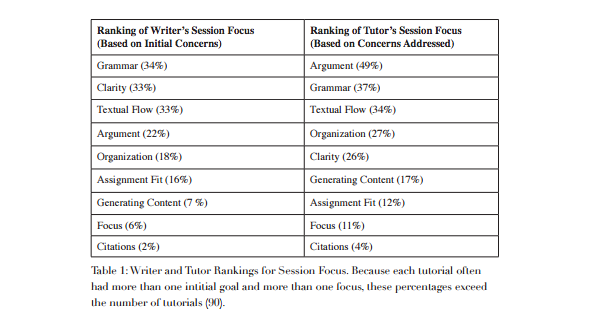

Their study’s focus is on how helpful the tutors are, which they assessed through looking at logs and keeping track of main areas based on writing concern definitions. These areas included no stated concerns, grammar, clarity, argument, assignment fit, citations, organization, textual flow, generating content, and focus and they were noted in their tutors’ logs. “Session goals,” as the authors chose to call them, would mirror our “what do you want to work on today,” or the logs we write at the end of the appointment.

We felt these categories or concerns were too broad, but upon further reflection we realized that this is not a fault of the study but just an issue that comes with the territory. Though anyone who writes anything is a writer, their concerns aren’t universal or easily collected into four questions or a series of tutor-defined categories.

Of the students who came to the University of Rochester’s writing center, a majority (34 percent) came in because they wanted to work on grammar. For tutors, the major concern was the argument of the writer’s paper. The chart used to show writers’ concerns compared to those of the tutor made us consider our own appointments and methodology — especially in regards to the categories they chose to represent.

Though we found fault with some of the methodology of the study, we did consider the ways we could adapt this study to our writing center and what it could tell us about our practices. When looking at the categories Raymond and Quinn split their logs into, we worried that the writers were going about this project too generally. For example, we considered how UCWbLers may define grammar — or even how we address those concerns with writers we meet with — may differ per person. IS punctuation part of this category or, considering the varying uses of punctuation, would it fit better under another category?

Here we considered the wordplay game some UCWbLers played during their training class.Tutors choose a word, they identify the different meanings of the word and how it can play into tutoring. There are different iterations of the game, but the main point is to focus on the slippage of terms — sometimes the writer will say they want to work on something, but during the appointment that is not what they actually want. This game allows the tutor to define the broad categories in relation to the papers or projects they work on with writers collaboratively, instead of allowing the tutor to do this individually.

The importance of defining terms that are important to the UCWbL is helpful for us as tutors, as well as peers; it enables us to understand the concerns of the writers.

As Amanda G., Chloe S., Maggie C., and I considered their findings, we concluded that if we were to do an experiment like Raymond and Quinn’s at the UCWbL, we might run into a few problems. Often the terminology that writers use when stating what they would like to work on — if they state it at all — does not fit their actual concerns, so doing a similar study here may be difficult. Sometimes writers come in with concerns about “grammar,” “clarity,” or “flow” but what these terms mean to them may be different from the actual definition, or the ones that we learned in training.

Overall, the goal of an appointment is to ensure that the writer gets what they want, as well as what they need. This article made us think of what we felt this research did well and what it didn’t; it did make us think of things we could do better. The language they use in detailing their study and their interactions with writers could have better addressed the needs of the writers individually, in our opinion. Though our writing center and the University of Rochester’s writing center may be fundamentally different, our goal — helping writers — is the same. Our core beliefs would help UCWbLers if we were to do a similar research project here. A focus on collaboration and using that as a means to work with writers per their needs was missing from the research done by Raymond and Quinn, we felt.They treat agency, a cornerstone of our policies and appointments, as something to be given instead of respected, existing long before the writer comes to us with a draft.

Remembering agency, as well as keeping writer concerns in mind in the appointment and out of it, are important things we continue to do at the UCWbL. But also leaving room for discussion, as well as collaboratively setting agendas to address all concerns of tutors and writers, could help us achieve our goal of giving everyone what they want.

Discover more from UCWbLing

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.