Latin scholars, how much are you bothered by the following statements?:

‘Chicago is the kind of town I’d like to live in.’

‘To hardly think is hard on the brain.’

In “Most of What You Think You Know About Grammar is Wrong,” former New York Times editors Patricia T. O’Conner and Stewart Kellarman discuss a few grammar ‘myths’ that could easily be mistaken as hard and fast rules because of how engrained they are in modern academic English. Their claims are simply more evidence for the fact that English grammar is a living thing that develops and changes over time. They point out that such pervasive taboos against split infinitives and endings with prepositions could be the result of the Latin influence on our language.

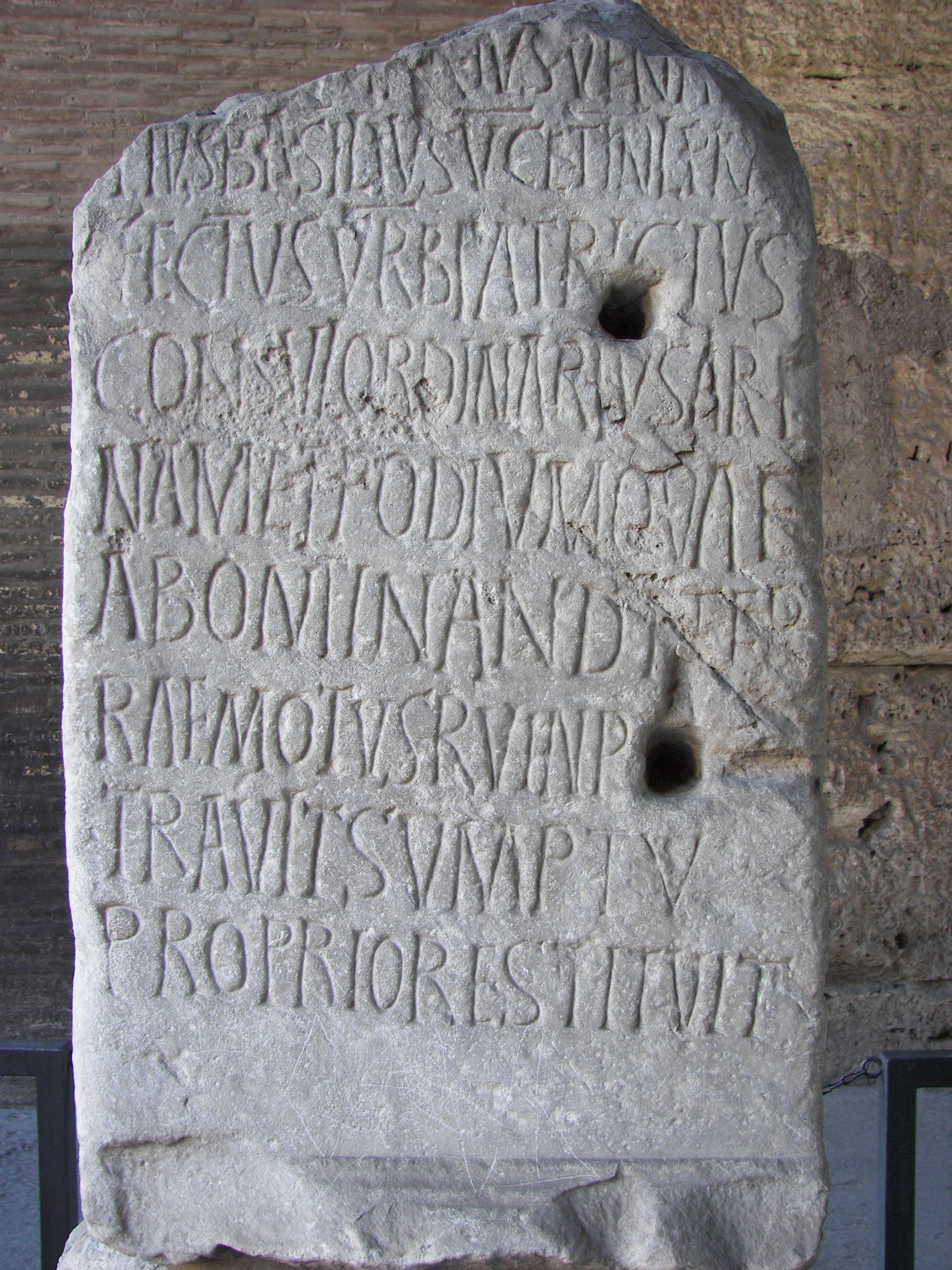

A Latin layperson myself, I didn’t know that Latin prepositions are placed strictly before their objects or that infinitive verbs are incapable of being ‘split’ as they are in English. O’Conner and Kellarman give us a bit of context for the influence of Latin on our Germanic language:

“Anglican bishop Robert Lowth popularized the prohibition against ending a sentence with a preposition in his 1762 book, A Short Introduction to English Grammar; while Henry Alford, a dean of Canterbury Cathedral, was principally responsible for the infinitive taboo, with his publication of A Plea for the Queen’s English in 1864.”

Despite the tenure these conventions still have in grammar and composition classes, O’Conner and Kellarman insist that in English, ‘to’ is closer to being an everyday preposition than to being a part of the infinitive verb. They cite Shakespeare, Wordsworth, and Donne as prime examples of writers who have successfully ended sentences with prepositions in highly regarded works of literature. It wasn’t until the practice suddenly fell out of style with academics that these uses were attacked.

Even more ambiguity surrounds the taboo of beginning sentences with conjunctions, a practice that both Roman and Latin rules prohibited, and an arguably more tried-and-true rule of thumb for academic writing. The amalgam of influences on grammar and sentence structure makes issues like this overwhelming, but it’s also part of what makes English such a unique language.

It’s interesting to me how gray areas like this can be so easily labeled and accepted as black and white rules over time. The phenomenon suggests to me that English grammar has the potential to gain or lose rules and conventions within the next few decades, especially given its struggle against advances in media and technology. How do you see yourself writing around 2043?

Discover more from UCWbLing

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.