This week in Conversation & Culture we spent some time talking about vocabulary level. An article we read about Chinese New Year celebrations had used the word “ruckus,” which conjured a lot of confused faces around the table. Ruckus – meaning a disturbance or commotion – is not exactly a common word, and most of the time we hear it in conversation as opposed to reading it in news articles. This prompted sharing some more off-kilter vocabulary that rarely makes it into print, let alone outside of certain geographic regions. For instance, in the South it is not uncommon to hear a person in their 50s or 60s describe something as cattywampus, which means askew or positioned off-center. Someone asked how to spell this, and no one was quick to offer a suggestion. It turned out none of us had ever had to write cattywampus; why is that?

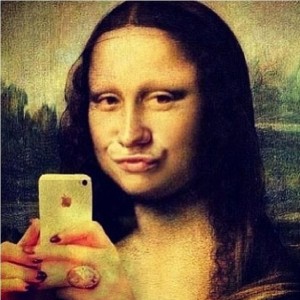

Imagine you are assigned a painting analysis on the Mona Lisa, and after a thoughtful description of the mysterious expression on her face you type this, “Despite the emotional complexity illustrated in the Mona Lisa’s face, her cattywampus nose detracts from the painting’s air of calm sophistication.” This will not be met well by most teachers for two reasons. First, the Mona Lisa’s nose is fine, so this is an absurd statement and, even with excellent support, it would be hard to pull off. And second, using the word cattywampus breaks the academic discourse we are all expected to wield as student writers. It is as if Huckleberry Finn walked barefoot through the Louvre. Not to say he shouldn’t or couldn’t, but sharp contrast in diction provokes attention, which may or may not be to our benefit.

This will not be met well by most teachers for two reasons. First, the Mona Lisa’s nose is fine, so this is an absurd statement and, even with excellent support, it would be hard to pull off. And second, using the word cattywampus breaks the academic discourse we are all expected to wield as student writers. It is as if Huckleberry Finn walked barefoot through the Louvre. Not to say he shouldn’t or couldn’t, but sharp contrast in diction provokes attention, which may or may not be to our benefit.

Academic writing asks that we be able to make arguments based in objective reality and provide support for them. What’s more though, is that there is an implicit demand for what is perceived as more sophisticated diction. Consider the following sentence: “Governor Romney’s dubious claim that President Obama ‘sold Chrysler to Italians who are going to build Jeeps in China’ was soon revealed as a lie that cast a shadow of doubt over his trustworthiness.” Now let’s change the diction: “Mitt said something sketchy[1] about how Barack sold Chrysler to some Italians that’re gonna do it on the cheap[2] in China. Can’t believe a word he says now.” If a professor reads the second sentence in your paper, it’s getting the red pen. However, talking like that to a friend or strangers around Chicago can come off as normal.

Why is conversational familiarity distrusted in an academic discourse? Can someone not be honest, objective, and well supported in their claims while speaking in this way? I am of the opinion that many people within academic institutions consider conversational diction to be spoken by the less intelligent, and therefore if you use it, your opinions are judged – rightly or not – as those of a dumb person. And yet more substantive arguments can be made. Conversational vocabulary is often less specific than a more academic equivalent, and can deny your paper clarity and eloquence. Furthermore, when you’re speaking in person, body language and tone add depth to expression that the written word lacks. Perhaps there are cattywampus opinions about who speaks how, but sticking to an academic discourse lends writers increased articulation that helps bring text to life. So grab a piece a paper, and go cause a ruckus.

[1] Sketchy – adj – Iffy; questionable; creepy.

[2] On the cheap – idiomatic phrase – Done inexpensively, often resulting in low quality.

Discover more from UCWbLing

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

2 replies on “Who’s Speaking? Who’s Listening? Who’s Writing? Who’s Reading?”

Hi, Walker! Your blog reminds me of an activity I’ve taken from WRD professor Chris Tardy to help tutors and teachers understand the challenges that English Language Learners face. She has students start free writing about their experiences learning other languages, and then half way through, she has students switch to writing in any language other than English. For those of us who are not multilingual, this is great activity to see what it’s like to try to write in a non-native language–we become severely limited in what we can say largely because of vocabulary restrictions. I think it’s good for all of us to be reminded from time to time about how hard it is to do college-level work in another language and that people’s vocabularies don’t always reflect the complex, sophisticated ideas they have.

^_^ thanks for commenting Lauri, I totally agree! It’s easy to interpret vocabulary as a representative of someone’s intelligence, even though that’s often not the case. That activity sounds entertainingly difficult and empathy inspiring; if someone asked to me to switch to Russian half way through a class, I’d be at a loss.