One of our mottos at the UCWbL is to meet writers where they are. This can mean where writers are in the writing process, the writing experience they have, or how they want the appointment to go. It is our job as peer tutors to be able to adapt to each writer, their personal preferences, and their writing styles. One of the many ways we can do this is by implementing hands-on learning techniques in our tutoring appointments.

Hands-on learning, sometimes called kinesthetic learning, can include anything from creating artworks based on ideas to charting out a mind map to just physically writing out an outline, draft, or paper. While everyone has a different preference for learning, hands-on learners understand concepts better when they have something physically in front of them. This learning style has the ability to develop a variety of skills that others do not. Many hands-on learners are proficient in problem-solving, have increased communication skills, and can more easily and openly appreciate different perspectives (“What is a kinesthetic learner?”). Especially as we move back to in-person appointments and tutoring, tactical learning provides “an opportunity for authentic sensory experiences” that were not as available to hands-on learners when everything was virtual.

When discussing hands on-tutoring specifically, it’s important to touch on the primary thinking differences between kinesthetic learning and tutoring. As Flower and Hayes’ “Problem-Solving Strategies and the Writing Process” explains, “Within the classroom, ‘writing’ appears to be a set of rules and models for the correct arrangement of preexisting ideas. In contrast, outside of school, in private life and professions, writing is a highly goal-oriented, intellectual performance” (Flower & Hayes, 1977, p. 499). To contextualize this, ‘writing in the classroom’ might refer to a more beginner stage of writing in which a writer was given all parameters and topics they must hit in any given assignment. However, in more advanced or professional writing, sometimes a writer is given a sentence or less of instructions, hopefully yielding a project consisting of many pages. This results in a composition problem in these professional or collegiate settings, or, the problem of what you will write about?

To help remedy this, Flower and Hayes suggest using heuristic procedures, which are focused in goal-setting and problem solving. So, in order to best practice kinesthetic learning, tutors should combine these two strategies to create strategies that are both sensory and goal-driven.

The benefits of hands-on tutoring are very reflective of the goals of hands-on learning. Every student learns differently and it’s our job as tutors to meet writers where they are, adapting and creating strategies for them in order to best help them. As Carol Severino and Jane Cogie theorize in “Writing Centers and Second and Foreign Language Writers,” we should take the approach of “informed flexibility,” instead of assuming all students operate similarly.

Some strategies that are both kinesthetic and heuristic-based include:

- cutting up the draft

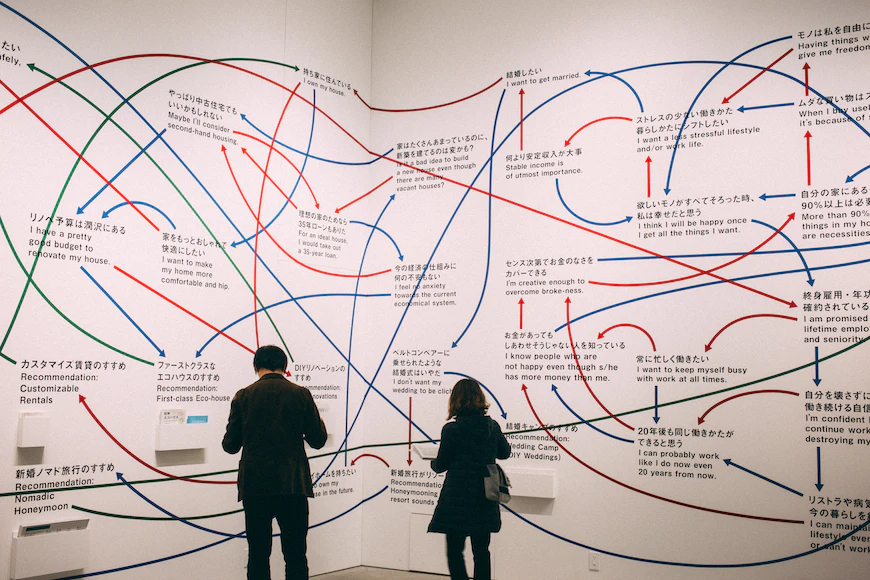

- making a mind map

- free writing with pen and paper

- color coding the draft

- drawing out main points

- physically writing a rough outline

All of these strategies are not only tangible, but are also directed towards the end goal, whether that be the specific conclusion of a given assignment, or simply the end of the project in general. These strategies may be useful to suggest in an appointment where the writer might be more of a hands-on learner and are great options in striving for the most personalized and specific version of tutoring, which speaks for the individual’s best practices and the ability of the tutor to best accommodate them. As John Bean reflects on in his essay, “Writing Comments on Students’ Papers,” “the writing teacher’s ministry is not just to the words but to the person who wrote the words” (Zinsser, 1988, as cited in Bean, 2001, p. 317).