Mad Libs are fun and zany, while traditional outlines can be tedious, limiting, and confusing. Although both involve filling in the blanks within a designated format, Mad Libs are meant to be illogical while outlines are not. Nevertheless, outlines don’t always help writers understand how ideas are connected and can even discourage revision by making the structure seem unchangeable. Because traditional outlining isn’t universally beneficial, here are three unconventional outlining alternatives.

Writing Wheel

“Outlines have long been used by writers to organize their thoughts before writing. Many college students, however, find this process too abstract.” (Rae 102).

Because traditional outlines are too conceptual for some writers, the writing wheel might be a better option. This method visually illustrates the relationship between the thesis, subject, and topic sentences, helping to make the writer’s ideas concrete. It can also be used for individual body paragraphs with the topic sentence in the place of the thesis and evidence as the spokes.

- Draw a circle and write the thesis around the edge. This is the wheel and allows the whole “vehicle to move” or gives the essays its purpose.

- Draw a small circle in the center of the original circle. Write the word that is central to the thesis in the smaller circle. This is the hub, the irreplaceable word or subject around which the paper focuses that and the thesis meaning.

- Draw lines from the smaller central circle to the edge of the bigger circle. Write topics or subtopics supporting the thesis on these lines. These are the spokes and can later be used as the focus of the body paragraphs.

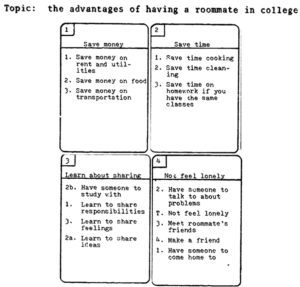

Box & Card Outlining

“The weakness of in the traditional outlining method is that it generally assumes outlining to be a fairly straightforward process, when in fact it is a complex interaction between four quite separable tasks” (Hubbard 61).

The purpose of traditional outlining may seem self-explanatory, as writers fill in the blanks with the appropriate information. However, the traditional method muddles the four tasks of outlining: gathering information and evidence, grouping similar information together, labeling those groups under a common idea with a heading, and organizing the groups into an order that flows logically. Box and card outlining are methods that allow the writer to separate and focus on each task more fully, ensuring greater unity and coherence overall.

- After freewriting on another piece of paper, write the topic at the top of the page.

- On another page, group similar words, phrases, or topics from the freewriting page together. These groups will become the subtopics. Cross out words or topics that do not fit within a group.

- Draw boxes for each subtopic and write a label/heading for the subtopic at the top of the box.

- Under each subtopic heading, refer to the groups made in step 2 to fill in the ideas that support and coordinate with each subtopic. If there is insufficient information, return to researching or consider revising the subtopic groupings.

- Order the groups logically and number them accordingly. These will become the body paragraphs.

Box outlining is shown above, but this method can also be used with separate note cards for each group. Using cards allows for greater mobility in step 5.

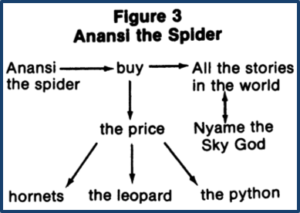

Array Outlining

“The major problem that teachers face with students who can’t outline is not teaching outline format, but teaching students to understand the material they have read” (Hansell 248).

Because writers sometimes struggle to synthesize and connect their ideas in traditional outlines, array outlining provides a possible alternative. This method is sort of like reverse outlining and allows writers to visually map how they believe their paragraphs and ideas flow into each other. Array outlining makes connections meaningful through its use of directional arrows and lines and ensures a pattern of comprehension by visually indicating how the writer’s ideas logically relate to each other.

- Start with the central idea/topic and write this at the top or center of the page. This is usually the title or subject of the paper. (Different colors can be used to indicate a hierarchy of importance.)

- Write associated subtopics of their body paragraphs around the central word. Draw arrows from the central word to indicate how a hierarchy and how the new subtopics relate.

- Continue branching from the secondary words to tertiary ones. The tertiary subjects can be evidence or examples. Arrows may also be drawn reciprocally to indicate mutual importance and interrelation between subtopics.

- Fill the page with as much information as necessary and cross out ideas that are irrelevant or unimportant until a logical flow of ideas remains. Compare the array outline with the draft and see if what the writer intended to express was actually communicated.

This method is traditionally used to display a reader’s comprehension of main ideas and narrative, but can also be used so a writer can determine if their topics are coming across clearly to readers.

Takeaways

Outlines are not universal, but they are also more than just hierarchical lists. They’re meant to “[act] as a temporary record of agreements, a field of reconsideration, a way to demonstrate new ideas and hold them in place while we discuss them” (Price 416). Because writers don’t always think of them this way, it’s up to us as tutors to “adopt and adapt specific strategies for each particular writer and their particular writing context,” to decide if outlining is an appropriate strategy, and to modify it to suit the writer’s process, exigence, and assignment. Outlining may not be as fun as a Mad Lib, but it doesn’t have to be so daunting either; it’s just another way that we implement strategies to “produce better writers along with better writing.”

Works Cited

Flower, Linda S., and John R. Hayes. “Problem-Solving Strategies and the Writing Process.” College English, vol. 39, no. 4, Dec. 1977, pp. 449-461.

Hansell, T. Stevenson. “Stepping Up to Outlining.” Journal of Reading, vol. 22, no. 3, Dec. 1978, pp. 248-252. JSTOR, www.jstor/org/stable/40028707. Accessed 30 Oct. 2018.

Hubbard, Philip. “Alternative Outlining Techniques for ESL Composition.” CATESOL Occasional Papers, no. 10, Fall 1984, pp. 59-68. Educational Resource Information Center, https://eric.ed.gov/contentdelivery/servlet/ERICServlet?accno= ED253065. Accessed 30 Oct. 2018.

Price, Jonathan. “Electronic Outlining as a Tool for Making Writing Visible.” Computers and Composition, vol. 14, no. 3, Dec. 1997, pp. 409-427. Science Direct, https://doi.org/10.1016/S8755-4615(97)90009-8. Accessed 30 Oct. 2018.

Rae, Colleen. “Before the Outline: The Writing Wheel.” College Teaching, vol. 34, no. 3, Summer 1986, pp. 99–102. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27558174. Accessed 30 Oct. 2018.