If you think that all of the skills we’ve learned while tutoring at the Writing Center will be useless after we graduate, think again. In my early days as a tutor, I was often frustrated with the tediousness of agenda-setting and writing appointment letters. However, the repetition of these tutoring techniques offer a consistent process that works every time when trying to craft and tutor a piece of writing. The reason this process has been cemented in me is because I use these same tactics outside of the Writing Center. Everyday in rehearsal, I actively apply tutoring techniques to my practice as an actor.

This fall quarter, I’ve had the pleasure of being cast in Eurydice, by Sarah Ruhl, at The Theatre School. This is a very poetic show that twists the original Greek myth of Orpheus to make his beloved, Eurydice, the main character. I was cast as Big Stone–one of the three members of the Chorus of Stones that the audience meets about 25 minutes into the show after Eurydice dies and enters the Underworld of Hades. This Chorus of Stones works like a Greek Chorus, narrating the events of the play to the audience, while also being an active part of the action. The three Stones (Little Stone, Loud Stone, and Big Stone) act like the servants of Hades who, in Sarah Ruhl’s adaptation, are depicted as children no older than 8 years old. In the director’s notes in the script, Sarah Ruhl specifically states that the Stones should be played like “nasty children at a birthday party.” Throughout the entirety of the play, they constantly snap, mock, and tease at the other dead characters (mainly Eurydice and her Father), particularly to reinforce the rules of the Underworld. Some of these rules include but are not limited to: rooms are not allowed, fathers are not allowed, sleeping and eating are not allowed, being sad is not allowed, singing is not allowed, etc. The simplest way I can contextualize the world of the Stones for you is through these rules–every soul in the Underworld gets “dipped in the river” of forgetfulness, so they can no longer remember the pain and joy of being alive. To be a Stone is to be an empty soul dipped in the River Styx, to have brain and memory development reduced to early childhood, and to simply exist in the eternal stink of the Underworld with no knowledge or memory of ever having a life before death. The only two souls in the Underworld that were partially dipped and still retain some memory are Eurydice and her Father.

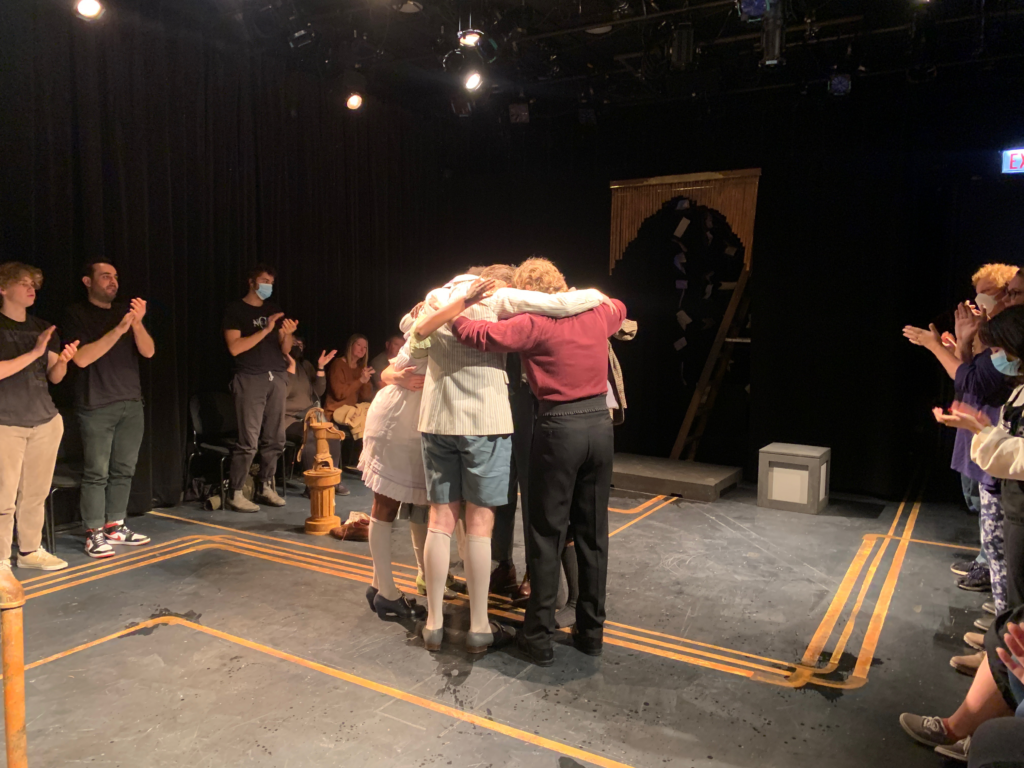

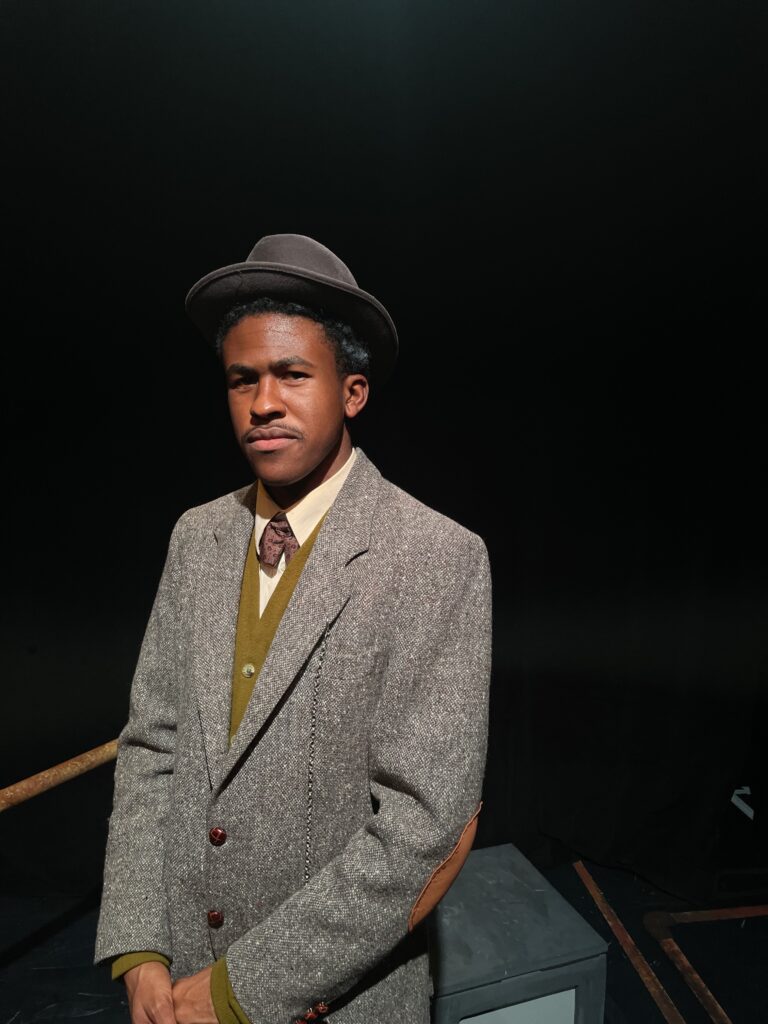

Right (Tryumph Williams as Little Stone)

Although this show is expansive, poetic, and complex, I hope that this summary provided a little bit of context towards my character and the world of the play. Yet despite all the fanciful details already given to us by the script alone, they can only come alive onstage through an actor’s technique. Words alone cannot tell a story; it has to be embodied, full of intention and specificity. How does an actor turn simple words of a script into a carefully crafted performance? Surprisingly enough, tutoring techniques at DePaul’s Writing Center have contributed greatly to my process as an actor. The three ways these modalities align include using a conversation-based approach to establish clear and safe relationships, adhering to the Hierarchy of Concerns, and completing the process of reflection.

The Relationship between Rehearsal and Tutoring

Throughout our peer writing training class and the numerous professional development meetings we undergo as tutors, we constantly implement the UCWbL’s core beliefs:

- Anyone who writes anything is a writer.

- There is no universal writing process that all writers (should) use.

- Writing facilitates communication and learning.

- Collaboration among peers is an especially effective mode of learning.

- All writers, no matter how accomplished, can improve their writing by sharing their work in progress and revising based on constructive criticism.

- Writers produce written texts in many different contexts, using many different genres of writing. Understanding these contexts and genres can help writers as they write (UCWbL)

What these beliefs aim to achieve is a deconstruction of many students’ initial perspectives about writing. I’ve had many writers begin their appointments with me saying something like “I’m just not a writer,” which is clearly not true, since they can and do write. Opening themselves up to tutoring can be a taxing, sometimes emotional process for students, especially culturally diverse writers and ESL students. According to The Writing Center Journal, students failing “to code themselves as ‘normal’ or perform within a band of normative expectations… are often dissected in all manner intellectual, philosophical, and psychological” (Denny, 2010, p. 106). A lot of times, they expect a teacher-student relationship out of peer tutoring, hoping to just get told what to change in their paper, only to fulfill the requirement of the class to make a Writing Center appointment in the first place.

At the start of every appointment, my goal is to establish a peer-to-peer relationship with the writer instead. We usually introduce each other, check in about our day in general, and then about the class assignment in general. After this rapport, I’ll describe my process as a tutor, preferring a conversation-based approach rather than a lecture-based approach to the appointments. Throughout the appointment, if a concern arises in the writing that might require rewording or restructuring, sometimes I’ll say things like “let’s figure this out together” as we dive in. Asking questions like “what do you think about this change?” and “how would you reword this sentence?” and “what did you mean by this?” can put writers directly in conversation with the tutor, guiding their own edits to best suit their needs. This establishes the tutoring space as one free from the “normative” expectations associated with “good” writing; “writing center practitioners must queer the dynamics that put forth particular codes of identity and intellectual practice as ‘normal’ and others as not” (Denny, 2010, p. 107). No one person understands their own writing and mind more than themselves; therefore, approaching each appointment as a conversation requires preparing adaptable tutoring techniques.

The fact is, the Writing Center core beliefs and the conversation-based approach to tutoring relationships are directly applicable to acting and the rehearsal process for Eurydice. In the first rehearsal, our ensemble created a list of group agreements that detailed specific ways we can keep each other safe in the theatrical space we created. The list included phrases like “Impact over Intent” and “any person can call ‘hold’ at any time for any reason.” From then on, we start every rehearsal standing in a circle and checking in about how we’re entering the space, what our access needs are, and where our touch boundaries are for that day. We then play a theatre game called “Pass the Clap” and slowly build an “Energy” chant we came up with together. These check-ins and warm-ups launch us into rehearsal mentally–letting go of the day prior–and physically. It establishes a professional ensemble relationship that ensures safety (I’ve been in theatre ensembles before that ignored these check-ins and warmups, and it made our group dynamic unclear, segregated, and chaotic). As we rehearsed and dissected the lines of the text, to understand the story better our director would ask us questions about our relationship to the words of the text. “What does that word mean to you?” and “how are you using this sentence to get what you want out of your partner?” and “what do you want?” were commonly asked of the actors in rehearsals. This allowed us free space to verbalize our impulses, communicating with the director who helps us dive deeper into the meanings of each moment. Questions like these avoid uncomfortable power dynamics and, in general, bad direction–which would entail simply telling the actor how to deliver the line. Great acting is more than delivery; it is embodying the life of the text. Hence, the collaborative conversation-based approach that I use at the Writing Center is extremely beneficial to the play rehearsal process.

Hierarchy of Concerns

One of the fundamental tactics for tutoring requires setting our feedback agenda items and sticking to them. Yet, many writers request feedback on a multitude of problem areas. Given our appointment time constraints, we use The Hierarchy of Concerns to quickly identify feedback points and create agenda items that reflect the most important ones. According to the chart attached below gathered from Engaging Ideas, the concern of highest importance in a writer’s paper regards assignment fulfillment. As tutors, it’s much more important that we help writers fulfill the requirements of their class assignment first, before focusing the rest of our time on smaller changes to grammar, punctuation, etc. In my experience, I’ll usually start my written feedback appointments with no prior knowledge of the student, their writing, their class, and their assignment guidelines. Referring to the Hierarchy of Concerns sheet helps to quickly pinpoint the most important agenda items to focus on regardless of what the assignment is:

The structure of this chart is extremely beneficial for guiding focus as a tutor, so I decided to apply this same ideology to my focus as an actor. The fact is, there is also a hierarchy of concerns for every individual actor, director, and crew member of a theatrical production. For Eurydice rehearsals, creating my own hierarchy of concerns helped keep my energy focused on my own work, trusting the process that the entire production company is undergoing. For example, my high level concerns include telling the story completely, fully committing to the action my character is taking, establishing and maintaining relationships onstage, blocking accuracy, pre-rehearsal/pre-show prep, and line accuracy. Notice, however, that none of these concerns address another actor’s performance, or the direction of the show, or the lighting/sound/set design, etc. As an actor, I have to trust that every person on the production team will do their job fully, and the only thing I can control is my own commitment to my own performance. This relates directly back to tutoring, as conforming to the standardized grammatical practices are less important as a tutor than making sure that the writer’s work is effective; by effective, I primarily mean getting their point across. At The Theatre School, actors are taught a technique called “Personal Poetry” when translating Shakespeare, putting it into their own words and using their own slang to convey the same message. Although academic writing isn’t poetry, it’s more important to highlight that the writer’s personal voice is shining through their writing and that it’s landing effectively. If grammatical errors hinder the effectiveness of their points, then it’s a greater concern to address; however, if a writer’s grammatical “error” isn’t a hindrance to their point and actually accentuates their personal voice, it’s not a huge concern for me as a tutor.

As an example of how the Eurydice production incorporated the hierarchy of concerns literally, I’ll describe one of our rehearsals. At around 7 weeks into rehearsals, the show was completely blocked and all our lines were memorized. However, there were many emotional beats and storytelling moments that still needed to be fleshed out with the other actors. As a result, our director split us up so she could work individually with the actors playing Eurydice, Father, Orpheus, and Child, while she sent me and the other two actors playing the Stones to a separate room to work on our own. Our director had her own concerns–the most important one for the time was to make sure certain storytelling beats were being emphasized in the performance by the other actors. She had to trust us Stones to work through our own performance concerns so that her energy could stay focused elsewhere. It then followed that the Stones and I came up with our own concerns as we worked together in a separate room: our main concern was “Fluidity of Movement”–we make many tableau’s throughout the show that work like choreography, and we needed to practice our transitions in and out of these poses so they felt smooth; secondly, “Blocking Accuracy” was of high importance at the time since we were preparing for tech rehearsals–this means that while we could alter our tableau’s, our positioning onstage needed to be set and consistent, since lighting and sound designers take their cues based on our blocking; the third concern was “Action Clarity”–this means deciding what action verbs are attached to each line (are the Stones mocking/teasing/pushing at the other characters, or joking/mystifying/pulling at them?); the lowest of our concerns was “Line Accuracy”, which is self-explanatory but still important. All of these goals worked in conjunction with one another to keep our rehearsal time specific and focused. By the end of rehearsal, our director had effectively worked through the storytelling beats she needed to with the other actors, and at the same time, The Stones and I had finished devising our scenes. Trusting the process and technique garnered through the Hierarchy of Concerns truly worked.

Reflection

Arguably the most tedious part of tutoring is writing the reflection letter at the end of each appointment. Many new tutors often report struggling with time management in regard to their appointment letters, myself included. Yet, reflection is just as important as the comments itself; summarizing feedback in a short letter is not only a useful tool for categorizing/organizing your notes succinctly, but it offers writers a comfortable lead-in to viewing their tutor’s comments. To me, the technique of writing these reflection letters is incredibly useful. For my own reflections, I always start with building rapport–it’s helpful for writers to have a clear connection to their tutor outside of the writing itself so they know it’s a real human being that they’re working with. Next, I’ll list the agenda items I focused on as though it’s the thesis of my reflection letter. Then, I’ll write a brief paragraph on each agenda item summarizing the points I discussed–while writing this, I’ll often review my comments in the word document or in the Online Realtime whiteboard space to make sure I’m summarizing points instead of repeating them. Lastly, I offer a brief paragraph on the writer’s next steps after addressing my comments; for papers that need more research for example, I’ll point them in the direction of Academic Search Complete or the DePaul Library for further assistance. It’s a simple four step technique that works every time: build rapport, write reflection thesis, summarize each agenda, and provide next steps.

As you may have guessed by now, this same technique is also directly applicable to the reflection process in rehearsals for Eurydice. As I mentioned in the “Relationship” section, checking into rehearsals as a group is a necessary activity for preparing us for rehearsal mentally and physically. Equally important is checking out of rehearsal every day. Step one is building rapport, which has already been established through checking in at top-of-day; still, even a simple question to the group as “how are we feeling?” can help reestablish a group dynamic unrelated to the rehearsal process. Step two is thesis forming, which is as simple as discussing what we worked on in rehearsal that day. Step three is summarizing each agenda, which extends off of step two; for example, during the week 7 rehearsal I described in the “Hierarchy of Concerns” section, at the end of that rehearsal, The Stones and I told our director what we had worked on, and then we quickly performed those moments for her so she could see them played out in the space. Lastly, step four is the next steps, in which we all reflect with the director and stage manager as to what the next rehearsal will look like (when we’re called, what we’ll work, if anybody has any upcoming costume fittings, etc.). Another ensemble tool we’ll use at the end of the day to circle back to our check-in activity is to all clap together; this entails standing as a group, rubbing our hands together, and all trying to clap together at the same time with no one person leading the clap. The conjoined effort to clap simultaneously connects us as an ensemble, while the crisp group clap itself serves as a button to end our engagement with the theatrical space.

Next Steps

Now that I’ve reflected on how I’ve incorporated Writing Center techniques into my rehearsal process, where do I go from here? It’s my personal belief that an actor’s work is never complete. Even during the run of the show when it is all completely blocked and teched, every performance may likely be different and each actor must be prepared to handle such differences. Some days may bring forth personal struggles that affect an actor’s ability to perform, which requires even more reliance on technique to keep actors present to the moment. The same is true for writing, as some days the words flow out of us easily, and others we must rely on technique to overcome writer’s block. At the Writing Center, we also believe that a “complete draft” is never really complete, as the writer can always learn more, or the piece can be workshopped or carried forward into new works. Similarly for actors, even after a show’s run is complete, the actor must prepare for their next audition. Just as I applied tutoring tactics to rehearsals, the same can be applied to every audition as well. When auditioning, it’s just as important to establish a clear relationship with yourself, your piece, and the people you’re auditioning for; it’s just as important to limit your concerns and focuses so you don’t overwhelm yourself in an audition; it’s just as important to reflect after each audition so you can better prepare for the next one or handle rejection.

The fact is, tutoring writing and acting are more similar than I could have ever imagined. While the Writing Center has made me a better tutor and a significantly stronger writer, I’m overjoyed at how it’s made me a better actor. In every appointment I get scheduled for and every role I get cast in, I know now that I can always look back to the techniques that tutoring has taught me. If you’ve read this far, I urge you to consider this: how have these techniques bettered other aspects of your life? You may surprise yourself. 🙂