Preface

I do not tend to direct particularly literary work. I think people often conflate Writing Center practices with editing plays. While I am a dramaturg and write dramaturgical analyses (and I love a rich, layered script), my directing strays towards camp and spectacle. I work sensorially and create experiences—I love directing puppetry, interactive theatre, plays where the audience eats food, productions with music that are confusing on the page but envelop audiences in person. My Writing Center tutoring and directorial practices are similar because they both center facilitation to reach a clear and engaging goal. Both honor collaborative agency and creation, guiding questions, and actionable notes.

The Contact Zone

Directing and tutoring live in the contact zone. While tutors and writers have different strengths and training, we are both students with a common goal in mind: writing something effective, clear, and that the writer feels confident about. Tutors are not professors, and we don’t judge performance; tutoring is mutual learning using information we both bring to the appointment. While directors try to come in prepared and with expectations, a flurry of other ideas inform a production’s direction. Collaborators have different areas of expertise that shift understandings. Adapting based on each other’s experiences is key in the Writing Center.

While everyone brings their work-related perspective, they also hold personal experiences and identities. In the contact zone, identities push against each other. Appointments and rehearsals are space for collective growth and development, informed by our experiences melding together; theatrical collaboration forces those involved to question what they know and depend on each other’s unique experiences. Facilitators must constantly evaluate shifting points of view. It is up to us to ask what our writers are bringing and how they influence us. In spaces that can be vulnerable and fraught, mutual agency and recognition of the contact zone allow growth rather than prescription.

Questions and Actionable Feedback

Neutral Questions

Notes and feedback are effective when they are actionable and collaborator-led. We focus on neutral questions in dramaturgy, and they transfer to tutoring. Open, neutral questions (“Why did you include this information?” vs. “Do you think this information is unrelated?”) allow others to reflect on their own work and intent. A writer is the only person who fully understands their work—reflecting rather than just changing what they’re told helps them find their solution, not the tutor’s first instinct.

Neutral questions can be scaffolded. I like to lead with a question and give feedback based on the answer. For example, if I ask, “Why did you include this?” and the writer says that they aren’t sure, I suggest deleting it. If they explain their reasoning, I recommend writing what they told me into their paper. Because writers came to their own conclusion and solutions, they can apply what they’ve learned to other writing areas.

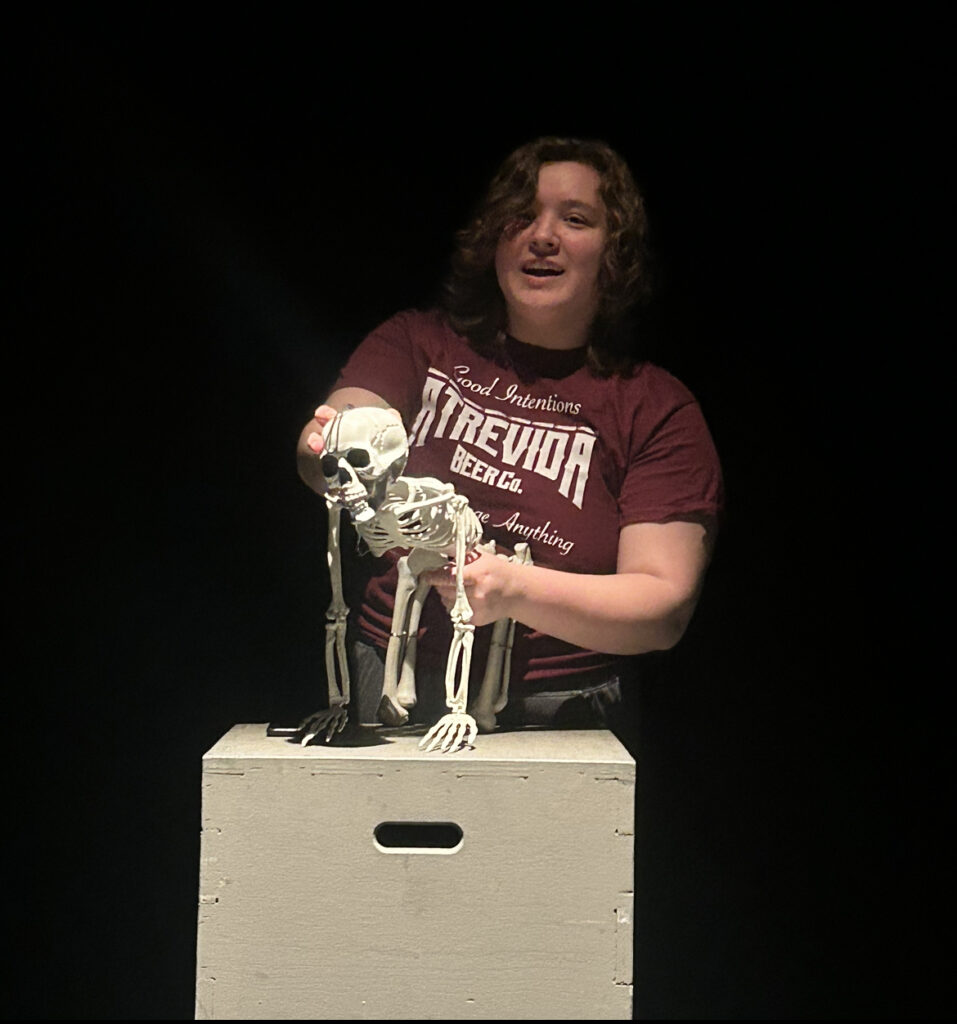

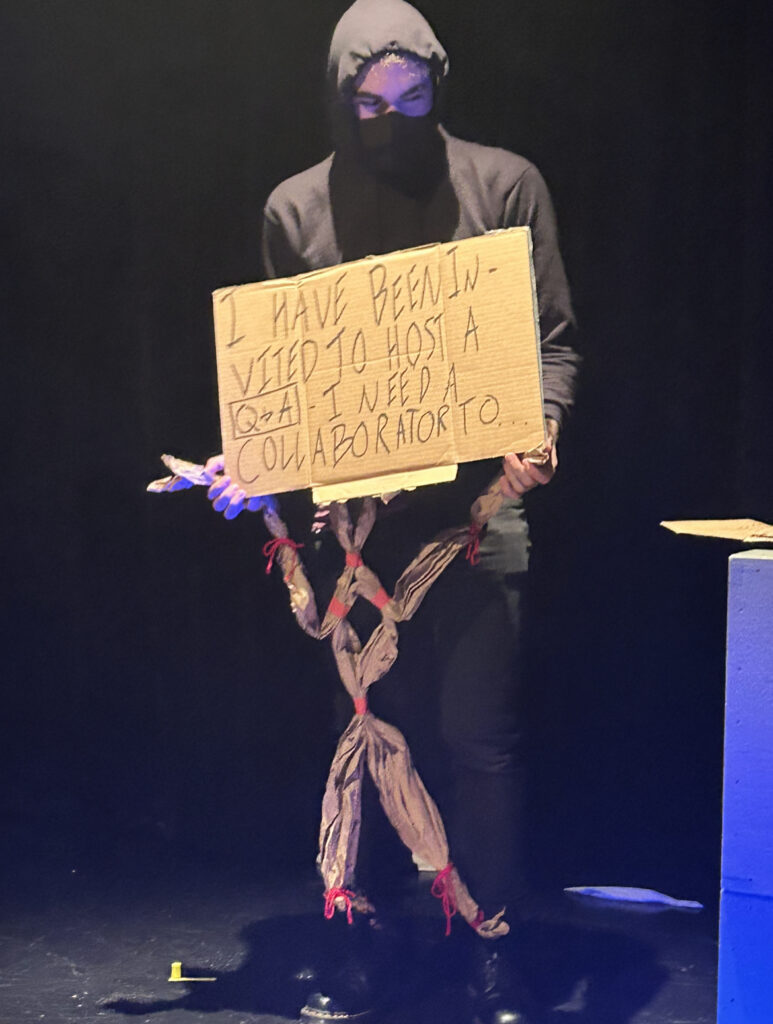

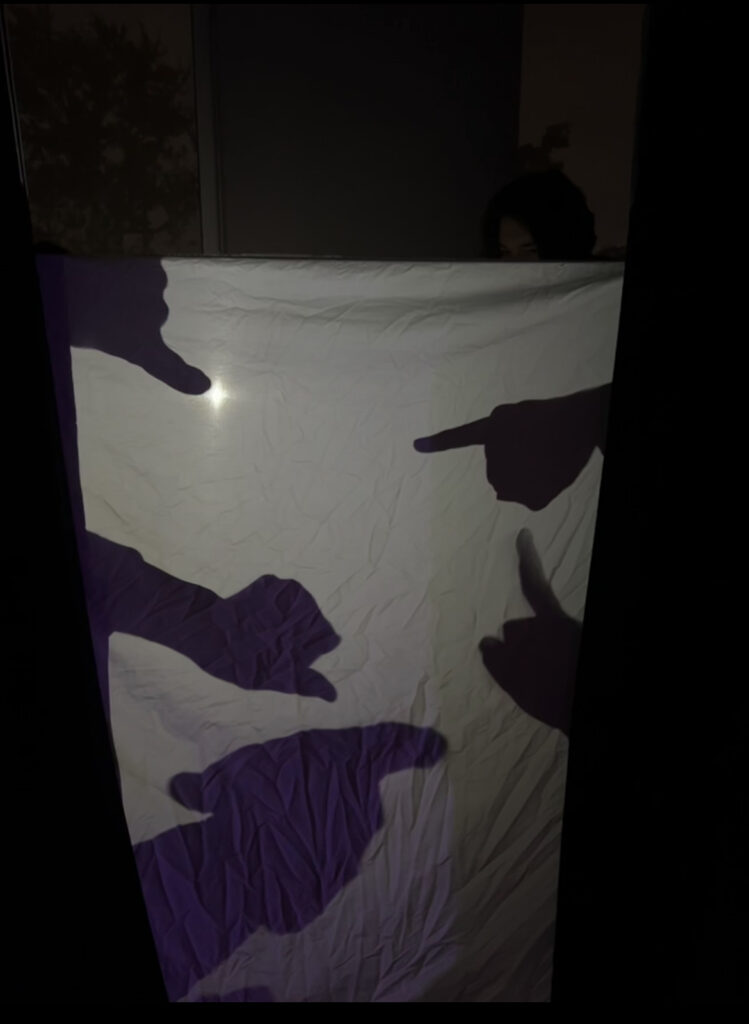

I just directed a devised horror puppet comedy cabaret (Ghost Cabaret), and I used question-based feedback. When writing and staging, I asked actors questions to develop story and imagery. I applied tutoring tactics to my directing, softening my language and guiding rather than prescribing. During rehearsals, every actor created a ghost character—the first question I asked was, “how did you die?” as a catalyst. Then, we developed the visual dramaturgy of the objects their spirits possessed. I asked, “how can you show your reaction in your puppet’s body?” and “why does your ghost need to tell the audience this information?”Questions formed the story, and asking questions in appointments helps writers articulate their own arguments.

Actionable Feedback

Feedback should be actionable in both tutoring and directing. Notes are for actors to pick up and apply immediately; writers can take feedback, apply it, and transfer it to other pieces of writing. Instead of ephemeral feedback, like “can you be sadder?” or the dreaded “vague,” I use active verbs that actors grab onto and positive language that writers move towards. My writing feedback is more active because of my directing. Instead of saying, “Can you be sadder?” to an actor, I would ask what they’re trying to do to their scene partner or the audience. I ask writers similar questions.

If I think actors could “be sadder,” active verbs include:

- Disarm

- Wound

- Convince

- Memorialize

In tutoring, if writing is vague, some active verbs for feedback could be:

- Specify

- Analyze

- Cite

Brainstorming and Devising

Brainstorming writing and devising theatre are both activity-based and flexible. Devising involves collaboratively generating ideas. Through games, movement exercises, and improvisation, directors and actors develop story and imagery. Activities reflect the story itself and cater to the ensemble’s needs. For Ghost Cabaret, I planned spooky activities to develop tone. I prioritized stage pictures, since it is a mini-spectacle. For a naturalist piece, I might facilitate character-based devising work. Ghost Cabaret’s actors were energetic, so I needed to use grounding activities instead of energizers. Activities depend on the group—if people are rowdy, quiet games can help get organized. If they like movement, gestural and movement-based activities are productive. If they want to get on their feet to generate scenes or if they like to write out scenes and then move, devising tactics shift.

Brainstorming at the Writing Center also depends on the writer’s prompt and the writer’s collaboration. Activity-based directing helps evaluate which brainstorming methods a writer needs. A creative project needs different strategies from a literary review. Because there is less time to build rapport than in a theatrical process, I try to ask writers what they need and act accordingly. An energized writer working on a personal reflection is a great appointment for drawing on a whiteboard, like how an ensemble of comedy majors working on a Halloween show needs ghost-themed multi-step generation activities; a quiet writer drafting a research paper may need to silently search for sources. Facilitating involves evaluating and acting creatively based on collaborators.

Glossary

-Dramaturgy: A production dramaturg connects audiences and a production, serving as an “outside eye” and maintaining textual/conceptual integrity. They provide context in the rehearsal room, look for problems, and create programming around the show.

-Notes: feedback given to actors during a rehearsal process

-Devising: an ensemble-written and staged piece

-Visual dramaturgy: In puppetry, a puppet’s appearance and materials communicate its meaning to audiences.

One reply on “Tutoring and Stage Directing”

Great post, Molly! So informative and thoughtfully organized. I learned a lot 🙂